1

When this story begins, in April 1942, in a Europe cast into fire and bloodshed by Adolf Hitler's War, Payerne, a fair-sized market town on the edge of the La Broye plain, not far from the border with Fribourg, is beset by dark influences. It had once been the capital of Queen Berthe, widow of Rodolphe II, King of Burgundy, who in the tenth century endowed it with an abbey church. Rural, well-to-do, the bourgeois town prefers to turn a blind eye to the recent decline of its industries and the people thereby reduced to poverty: five hundred unemployed to haunt it out of five thousand inhabitants born and bred.

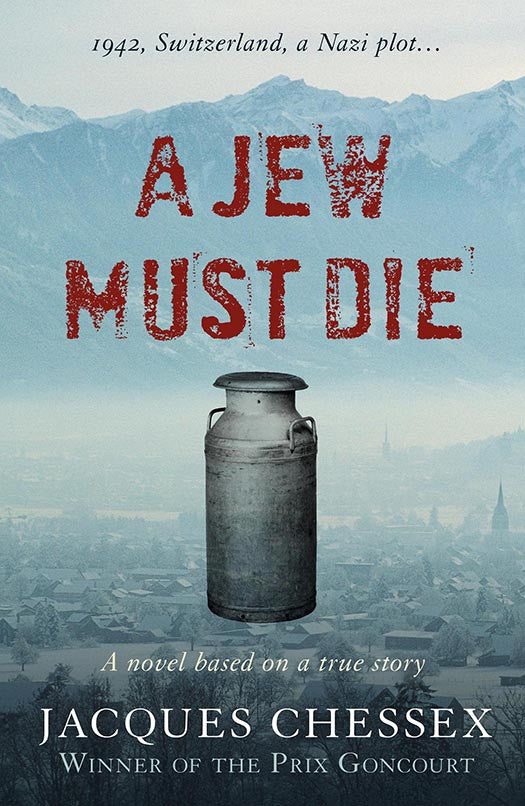

The cattle and tobacco trades are the source of the town's visible wealth. But pork-butchery most of all. The pig in every shape and form: bacon, ham, trotters, hocks, sausage, sausage with cabbage and liver, head cheese, smoked chops, pâtés, ears, minced liver. The emblem of the pig dominates the town, lending it an amiable, contented air. With rustic irony the inhabitants of Payerne are called "red pigs". But dark currents flow unseen beneath the assurance and business bustle. Complexions are rosy or ruddy, the soil is rich, but covert dangers lurk.

The War is far off: such is the general view in Payerne. It concerns others. And in any case the Swiss Army ensures our safety with its invincible battle plan. Our elite Swiss infantry, our mighty artillery, our air force as effective as the Luftwaffe, and above all our impressive anti-aircraft defence with its 20-mm Oerlikon and 7.5-cm flak guns. Fortifications all across the difficult terrain, heavily armed strongholds, toblerone anti-tank lines and, if things should go wrong, our impregnable "national redoubt" in the mountains of the Vieux-Pays. It would take some cunning to catch us out.

And then, when evening falls, the blackout. Drawn curtains, closed shutters, every source of light obscured. But what is obscured, and by whom? What is there to hide? Payerne breathes and sweats in its bacon fat, tobacco and milk, the meat of its herds, the money in the Cantonal Bank, and the town's wine that must be fetched from Lutry on the shores of distant Lake Geneva, just as in the days of the abbey monks - the same wine that for almost a thousand years has brought solar inebriation to a capital set in its vanity and its lard.

In spring, when this story begins, all around is lovely, with an almost supernatural intensity that contrasts with the heinous events in the town. Remote countrysides, misty forests at dawn, smelling of chill wild creatures, game-rich valleys already filled with fog, the strum of the warm breeze on great oak trees. To the east the hills close in around the outlying houses; the rolling landscape unfolds in the green light, while on plantations, stretching as far as the eye can see, tobacco is springing up in the wind from the plain. And the beech woods, open woodlands, pine groves, thick hedges and bright coppices that crown the Grandcour hills.

But evil is astir. A powerful poison is seeping in. O Germany, the abominable Hitler's Reich! O Nibelungen, Wotan, Valkyries brilliant, headstrong Siegfried; I wonder what fury can be instilling these vengeful spirits from the Black Forest into the gentle woodlands of Payerne: the aberrant dream of some absurd Teutonic knights assailing the air of La Broye one spring morning in 1942, as God and a gang of demented locals are taken in, once again, by a brown-shirted Satan.