What happened

November 24, 1971

As the 727 taxied down the rain-damp runway of Portland

International, the man in 18C stubbed out his third unfiltered

Raleigh and passed a note to the stewardess, a honey blonde

named Susan who’d strapped herself into the vacant seat across

the aisle.

Anticipating another clumsy come-on, she quickly covered

her name tag and took the note, flashing him a polite dropdead-

creep smile. Phone numbers scribbled on the back of

business cards, inappropriate comments about her legs, and

men ordering Dewar’s, splash of soda, without once looking up

from her breasts were occupational hazards she’d long since

learned to fend off with a diverse arsenal of bitchy half smiles,

beverage choice queries, and requests to buckle up and take

seats during turbulence. She figured that as soon as the plane

hit cruising altitude and she went to roll the drink cart down

the aisle she’d just toss the unread note into the trash. But

when she examined the intricately folded note and felt its

moist edges she knew she had to open it and see what was

inside, maybe share the contents with her fellow stewardesses.

It read: I have a bomb in my briefcase and I am prepared to

use it.

Her hands shook. She read it again, the words popping

inside her brain like tiny mushroom clouds: I have a bomb in my

briefcase and I am prepared to use it.

She took another look at the man, sitting cool like Robert

Mitchum under a haze of cigarette smoke, Ray-Ban Wayfarers

parked on his narrow face. He had on a dark suit and a skinny

black tie he’d wrestled into a full Windsor and jabbed with a

pearl stickpin. His hair was perfect and for the moment his

name was Cooper, Dan Cooper, to be exact.

Susan gathered up the gold cross that hung around her neck

on a chain and pressed the cool metal to her chapped lips to

stop her hands from shaking. For a brief moment her thoughts

drifted to her fiancé, a pipe fitter from Tacoma who’d been

after her to quit the airline.

“Do you understand?” Cooper asked, giving her twin reflections

of her own terrified eyes in his mirror shades.

She nodded and, like Dorothy in some terrible Oz, tapped

gold to enamel three times, hoping for some magic to pull her

out of this bad dream. But nothing happened and she let the

cross drop.

“Good,” he said, sitting back and stroking the briefcase on

his lap. It occurred to him that there would be no going back,

that this aluminum tube with wings slicing through the clouds

and mist might be the last thing he saw. And so he sucked in

the stale cabin air and lamped the neat rows of seats through

the twilight of his shades, taking in the dozens of heads Gforced

back and tenderly exposed above the seat cushions like

eggs in a carton. The cabin filled with the mindless chatter of

people on their way to Seattle anxiously putting words and

smoke into the stale air in the hope that it would somehow

negate the nagging possibility of a crash or some other disaster

– pilot error or say a duck sucked into the engine. He sat,

watching and listening to the nervous fraternity of lonely passengers

filling the empty space with the ordinary laundry of

their lives – the kids away at college, Maytags, the new lettuce

diet, the lonely guy at the office who finally got his ashes

hauled, Vietnam, breast cancer, Nixon and China, how the new

Buicks don’t hold a candle against the old Buicks, Muhammad

Ali, orthodontia, coffee stains on the stove top, church bake

sales, that Jonathan Livingston Seagull book, tax deductions,

beer cans left to ring end tables in familiar patterns, heart

disease, tax shelters, cheap weekend getaways, Idi Amin, college

tuition, gas bills, Evonne Goolagong, UFOs, electric crockpots,

lumbago, the wife and kids, and what exactly that song

“American Pie” was all about.

As the strange swoon of gravity denied sent a hush through

the cabin, Cooper decided to twist the fear blade a little deeper

and so he tapped the stewardess on the arm and opened the

briefcase. “See,” he said, holding two stripped wires. “I touch

these and the shit hits the fan, honey.” The plane skipped and

his hands swayed inside the briefcase, the wires almost touching

as he eased the lid down.

“I understand,” she mumbled.

“Now I want you to write down what I say and trot it up to the

captain so we can get this thing started.”

Her hands trembled as she pulled a pen and drink napkin

from her apron and readied herself.

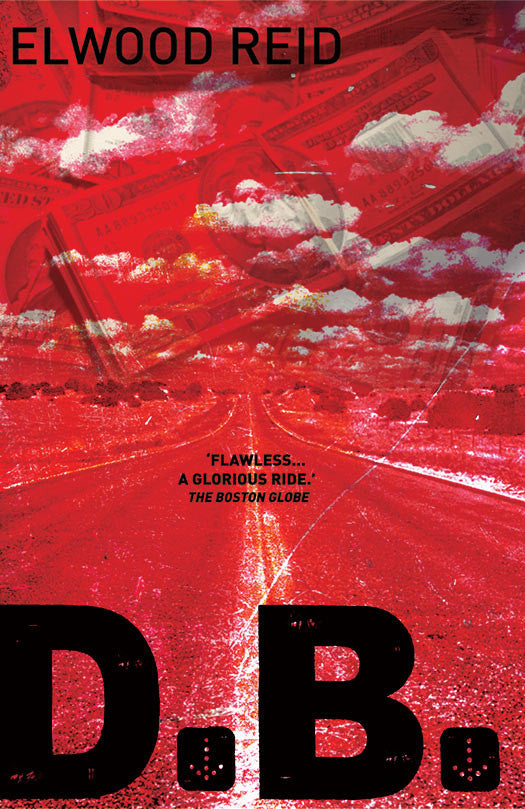

“Okay,” he said. “Now here’s what I want. Two hundred

thousand dollars in used bills and I want ’em in a knapsack.

Two back parachutes, two chest parachutes. After we refuel,

passengers go free. No police. Oh, and say takeoff from Seattle

by five. You got all that? Good. Now nod that pretty little head

of yours and gimme some smile.”

When she’d finished scribbling the message down she nodded,

unbuckled, and stood unsteadily, quickly looking around

to see if any nearby passengers had heard them. They had not.

She was all alone, with the blooming dread of what the man

had just so calmly dictated to her. And then there was the note,

I have a bomb in my briefcase and I am prepared to use it.

“Go on,” he said. “Hustle up there and bring the note back.

I need it for my archives. But first I want a highball, plenty

of ice.”

She lingered a minute, gawking at him, waiting for some

cruel punchline or smile. But none came. He wanted a drink.

He had a bomb.

Cooper stared right back, thinking: Boom motherfuckin’

boom! He’d always been good at tough thoughts and it worked,

because she brought him a highball and then made her way

toward the cockpit, rushing past the unsuspecting passengers

as the plane punctured the clouds on its way to Seattle.

From his smoky perch in the back of the plane Cooper

sipped his drink and got into character, trying to imagine them

all dead and scattered into the air, bits and pieces of them

seeding clouds, raining down like fertilizer.

Before: the name he’d given at the ticket counter was Dan

Cooper. It was not his real name, nor was it his first choice.

He’d briefly toyed with Rip or Quint but ruled them out as too

memorable, settling finally on Dan Cooper; a name with just

the right amount of generic menace. Dan Cooper sounded

like the sort of guy who might hijack a plane the day before

Thanksgiving and Dan Cooper would have a bomb and he

would ask for money and they would give it to him, because on

this gray day the man seated in seat 18C calling himself Dan

Cooper did not give a shit if he lived or died. He was tired of

mediocrity and the long flat road that his life seemed to be

speeding down and he had arrived at this plan, as a drowning

man flails for a towrope across riptide and chop. The plan was

pure, a thing to hone and polish and stick to if deliverance was

to be granted, and the minute he’d stepped onto the plane and

spotted the unoccupied backseat, he’d steeled himself for the

worst that could happen, be it crash or cowardice on his part.

That there would be no future for him or anybody else on the

plane – no Thanksgiving Day turkey, creamed peas, oyster stew,

or ginned-up relatives sleeping in recliners – was of no consequence.

Dan Cooper was getting the hell out. End of story or

maybe the beginning, depending on how things sorted out.

In the cockpit Susan relayed the message, her voice cracking

with every bump and bang of the fuselage as Captain

Yount instructed her to look for a gun and note the hijacker’s

demeanor. “Can you do that for me, Susan? I need you to be my

eyes and ears, size him up. We need to know what kind of

maniac we’re dealing with here.” She nodded, taking comfort

in Captain Yount’s square-jawed calm as he said, “Be brave,

Susan.”

She exited the cockpit and noticed that her knees had

stopped quivering and that she was able to meet the passengers’

curious stares. But as she neared the back of the plane

and saw Cooper waiting for her, hands resting on the briefcase,

she felt her heart surge into her throat.

“Are we on?” he asked.

“Yes.”

He plucked the note from her fingers and dropped it into

the watery remains of his highball, stirring until it became

mush. “No funny stuff this way,” he said, lighting another

cigarette.

He knew he had to scare her and so he opened the case and

gave her another brief snatch of the coiled wires and batteries

and dynamite-looking cylinders strapped inside. “Hell in a box,”

he said, still with the crooked grin. He pointed at the seat next

to him, motioning her to sit as the engines strained, blanketing

the cabin with their drone.

She sat.

And Cooper knew he had her and that his plan would work –

it would all work. He would get the money and parachutes and

he would disappear. It would be his grand gesture, the last

great thing. He pushed up his shirtsleeve and read the rules

he’d ballpointed across his wrist.

Be cool.

No guns.

Don’t take any shit.

So far so good, he thought. The plane continued to climb

momentarily over the storm clouds, the cabin filling with bright

bars of light. A silver-haired man three rows up turned to have

a look around. His face was toppled with sun, maybe too much

booze, and he was sweating, his tie jerked down, generous

thighs squeezed into navy slacks. Cooper nodded and the man

rolled his eyes and shrugged as if to say he was just getting

by and that it was enough that he rose every day to answer

the bell, kick back the stool, and tap gloves with what he called

his life.

Susan rose and Cooper turned on her. “Where do you think

you’re going?” he said.

She pointed at his glass. “You want another drink, right?”

“Exactly.”

A minute later she returned with another highball and tried

to see if he had a gun in his coat or a wedding band on his

finger – some telling detail she could report back to Captain

Yount about – but her eyes kept returning to the briefcase.

“Tell you what,” he said, lowering his shades. “Trot back up

there and tell Captain America I’m not foolin’ around here.

Tell him we’re not landing until the money and chutes are

ready. And remember, any funny stuff and we all go to pieces

together.”

She nodded and again made the trip to the cockpit, pausing

every other aisle to stare into the pool of each passenger’s

lap as she tried to get a handle on the situation and the possibility

that they might all be blown and scattered in the wind.

Instead she focused on the little things – pilled seat arms,

magazines sliding under seats, and the incredible dandruff of

the man in 7B.

Captain Yount was on the radio when she entered the cockpit,

his brow now damp with sweat, the copilot too focused on

the controls and gauges. Captain Yount told Susan to stay calm,

they were doing everything they could to meet the hijacker’s

demands. She did not believe them.

She hurried back and approached Cooper, mustering all her

poise only to see it crumble when he looked up at her.

“Well?” Cooper said. “Did they say how long?”

“He wants you to know that we’re doing all we can to make

this happen,” she said. “He doesn’t want anybody to get hurt.”

“That dog don’t hunt, sweetcakes. I want my demands met

sooner rather than later.” He pinched the Raleigh dead,

dropped it into the ashtray, and pulled another from the pack.

He motioned for her to light it, saying, “Now, how about giving

me some fire.”

She did. Their fingers brushed as she whipped the match

away, snapping it with a practiced snap of the wrist.

He took a long pull, let his face leak fresh smoke, and said, “I

sure hope we don’t have a hero behind the controls.”

Susan told him Captain Yount was a good man who was just

trying to do his job.

He pointed for her to sit again.

Two hours later, after circling in a holding pattern, the plane

landed in Seattle and taxied down a runway lined with waiting

vans, fuel trucks, and luggage tractors. He saw sharpshooters

crouched along the terminal roof like bland gargoyles, breathing

in between heartbeats, and inside the terminal stood men

Cooper figured to be FBI agents, their faces pressed against the

aluminum-frame windows, fogging the glass.

After a delay a courier car containing the requested chutes

and cash approached the aircraft. As instructed, Susan met

the car and transferred the chutes and bag of money, dragging

them past the rows of nervous passengers to the back of the

plane, where the man in the black suit and Wayfarer shades sat

holding his wires, waiting.

“Good work,” Cooper said as Susan dropped the chutes

and sack of money. He inspected the chutes quickly and then

snapped open the sack and allowed himself a moment of pure

gloat as he fingered a brick of twenty-dollar bills. “Okay,” he

said, pointing at his fellow passengers. “Get them out of here.”

Susan nodded and went to the cockpit. Minutes later Captain

Yount came on the PA system and instructed the passengers to

begin deplaning, his voice cool and reassuring.

They rose like churchgoers popping up from pews at the

first organ blast of the doxology, clutching at coats, purses, and

attaché cases, a few glancing at the man in the back with puzzled

expressions and the dim awareness that something bad

had happened or was still happening or was about to happen.

But as the people in the front of the plane began draining out

the door, down the steps, and onto the tarmac, squinting into

the lights, even the rubberneckers were pulled out into the

damp night as a stewardess wished each of them a happy

Thanksgiving. And like that they were gone, leaving the cabin

and crew to Cooper and the next phase of his plan.

When the hatch closed and the fuel truck backed away,

Cooper gave Susan instructions to relay to the pilot, telling him

to chart a course for Mexico City. She looked up and down the

empty rows of seats and the small litter of departed passengers

before pulling her eyes back to Cooper. “Mexico City’s nice,”

she said. “It’s warm and . . .”

“Goddamn right it’s warm,” he said. “And it’s not here.” He

pointed out the window.

“But why?”

He grinned. “I like that,” he said, tapping the briefcase. “Not

too scared to ask questions.”

She frowned, her chin no longer shaking, eyes dim and red.

She gave him a tiny nod and he went on. “Now here’s how

we’re gonna do this. I wanna go low – ten thousand feet, no

more, no less. I want the flaps at fifteen degrees – fifteen

degrees or, hell, I don’t need to tell you what’s gonna happen.”

He pointed at the briefcase, made a little boom sound. “Then I

want you back here with me for takeoff. Okay?”

She whispered okay and trotted toward the cockpit, stopping

to whisper to the dark-haired flight attendant before parting

the first-class curtain and disappearing.

Cooper turned his attention to the chutes, spotting the bad

one right away. “Fucking amateurs,” he said, tearing it out and

snipping the cords to bind the money sack to him. The others

looked good and the money felt nice and heavy – if not two

hundred, then close.

Ten minutes later the jet circled back onto the runway,

engines firing. Cooper waved good-bye to the rigidly silhouetted

John Q. Law types watching him from inside the bright

terminal, their hands on radios, just itching to give shoot

orders, the very same men who would be looking for him,

scouring the land, crawling through the plane dusting for

prints, spitballing possible motives, and interviewing oblivious

hostages, sifting for that criminal needle in the haystack. He

wished them lots of luck.

When he turned around Susan was standing a couple of

yards away, broken and awaiting further instruction.

He pointed. She sat. Then the plane muscled off the ground

and began its steep climb as Cooper stared out at the smudgy

blur of lights.

When they had stopped climbing at ten thousand feet he

told Susan that he wanted her to clear out of the cabin and go

up front with the other gals. She hesitated, pointing at the

briefcase containing the bomb.

“You wanna know how it’s going to end?”

She nodded.

“I’m about to find out,” Cooper said. “Now trot up there and

pull the curtain.”

For a moment he considered letting her in on the joke and

telling her that the dynamite was really a couple of old road

flares strung together with some colorful phone cable and a

radio tube he’d pirated from a twenty-inch RCA he’d found

abandoned behind his trailer. But he decided not to. It was best

to leave her scared and sure of her own heroism as she vanished

behind the first-class curtain like a magician’s assistant,

trembling with anticipation.

For a few long moments he just looked out the window,

enjoying the plane minus the passengers as he replayed the

dozens of jumps he’d taken over the humid jungles of Vietnam,

a world away from the ocean of fir trees, brush-tangled hills,

and twisted creeks of Washington that waited, cold, dark, and

wet below. Here it was, he thought, one of those moments in

life at which you arrive totally unprepared. But his demands

had been met and there was the money and all his tough talk

and months of planning. Certainly no going back.

It was time to jump.

When he rose and checked the chutes a second time he felt

that dead, sapped-out feeling creep into his legs – the one that

had enabled him to jump despite the presence of snipers waiting

for him under vine-ridden blinds, ready to shoot his heart

out expertly. He would be the dangling man all over again, a

piece of meat on a string caught between earth and sky. But

this time there would be no gunfire, just the long run to the

border, where some new life awaited him.

When he went to snap rubber bands over his pant legs and

shirtsleeves he discovered that he’d somehow forgotten to

wear the jungle boots he’d bought from the Army surplus

store. Instead he had on his house shoes, a thin pair of oxblood

penny loafers with bad stitching. He kicked at seat backs, cursing

his stupidity, until his toes hurt and he realized that there

was no option but to suck it up and soldier on, boots or no

boots. So he said fuck it and inventoried his pockets, feeling

the reassuring lumps and bulges of the waterproof matches,

barlow knife, Hershey bars, compass, waxed twine, aspirin, leather

gloves, wool watch cap, and the tin flask of bourbon he’d

carried during the war. He went to examine the rear hatch and

pressed his face to the tiny window, hoping to see the lights of

Merwin Dam or the dull glow of snow on Mount Saint Helens.

But there was only gray-black sky – an eternity of it.

He took hold of the red hatch handles and pulled down. A

blast of cold air quickly filled the cabin and sent alarms buzzing,

lights flashing. His ears popped and the plane bucked as

the captain’s voice came over the PA system. “Is everything

okay back there? Anything we can do for you?”

Cooper let go of the hatch, rushed over, and grabbed the

interphone and said, “No!” He waited, eyeing the curtain, half

expecting the copilot or one of the stewardesses to rush back

and stop him. But they left him alone and so he charged the

hatch again, shoving with every fiber in his body until it cracked

open a few feet and another wave of cold air swept through the

cabin, launching stray cocktail napkins and sending discarded

newspapers flapping around like trapped birds. He kept pushing

until the stairs snapped into place, the wind punching him

against the door frame, tearing at his chest and legs.

He took a moment to steady himself, his hands tugging and

checking the chute, pulling on the cord that held the money

sack as he looked down and forced his legs to move, sure that

at any moment he would be blown off into the night, sucked

through the engine turbines and transformed into bloody

ribbons. The first step was going to be a bitch, he thought, no

retreat.

He placed one foot on the tread and much to his surprise his

grip held even as he ventured another cautious step and then

another until there was nowhere else to go except down into

the howling void.

And so he pushed off and fell, tumbling past the roar of the

727’s engines into the rip of wind and rain that whipped his

hair back and snatched the half-empty pack of Raleigh unfiltereds

from his jacket pocket and instantly numbed his face

and fingers and straightened the narrow black necktie until it

stood behind him like a noose that would jerk him away into

the nothing as he spun through clouds and sheets of hard rain

toward the green rolling hills of the Columbia River valley far

below.

But there was the money, an enormous encouraging hand

slapping his back as he pumped his hips into the cushion of air,

screaming until his lungs fell empty and his body felt as if it had

been sprung from some dark cage into the roar of a waiting

coliseum.

Down he went, hurtling toward the sprawl of lights and trees

and interstates lit with lonely taillights of tractor trailers and

cars full of families traveling to Thanksgiving celebrations the

following day where they would wake to the smell of risen

bread and roast turkey and to the newspapers announcing his

deed and the $200,000 he’d run off with or died trying to.

So he pulled the rip cord. The chute fluttered and then

popped open, jerking him back and jumpstarting his dead

heart with a snap. The easy part was over, he thought, time to

take the money, get lost, and slip down the rabbit hole and

vanish.