MONDAY 13 OCTOBER 1952

1

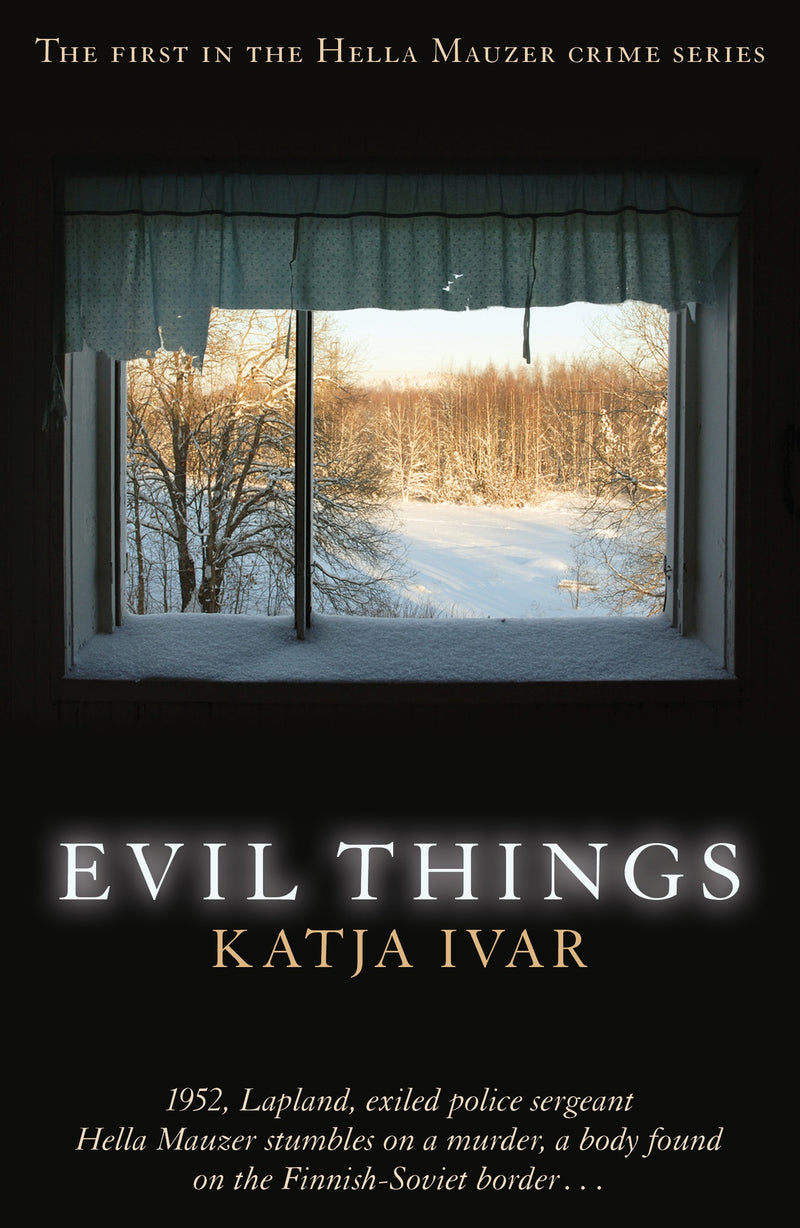

She had to squint hard to see where the village was. Just a tiny speck of grey on the map, buried deep in the crevices of that ancient, frozen land. Surrounded by marshes and hills bristling with low, crooked shrubs typical of the permafrost. Inhabited mostly by Skolt Sami, indigenous people who lived off the land, hunting and fishing. Not exactly a tourist destination.

She must have been out of her mind to have insisted on going there. And to do what? To solve a crime that her boss didn’t even believe was one.

“It sounds just like an accident to me,” Chief Inspector Eklund said, his full lips pursed. He was standing next to her by the map that hung on the wall of his newly refurbished, obsessively clean office that reeked inexplicably of fish oil.

“It could be a crime,” said Hella. She was careful not to sound too sure, too forceful. Eklund didn’t like her bossy attitude, as he called it, and for better or worse she was stuck with Eklund.

“An old man, practically a recluse, goes missing from his home. Not a crime. He probably got lost in the forest, or drowned in a marsh. Or went over the Soviet border like they all do, got drunk on local Kremlevskaya and forgot who he even was. There’s nothing to it.”

“He was born in that forest. He couldn’t possibly have got lost. And I don’t believe he went binge-drinking with the Soviets either. He left a young child behind. His grandson.”

“Oh, that’s why!” Eklund lifted an accusatory finger. “He left a child behind! Of course, that immediately makes you think he was the victim of a crime. Mind you, I understand why you’d react like this, I really do, but that doesn’t make

his disappearance a crime. Accidents happen. All the time. And that old man probably wasn’t the doting grandpa you imagine.”

Lennart Eklund went back to his desk and dropped into his brand-new swivel chair, making it squeak under his weight. For him, this conversation was over. Not for Hella. She went on, her voice loud and clear, all her prudent resolutions forgotten.

“So this priest’s wife, Mrs Waltari, writes to the police saying that an old man has gone missing, leaving a child behind, that it’s been six days since he was last seen, that she’s worried, and you’re telling me we do nothing? We just file her letter in one of our neat archive boxes and forget about it?”

Eklund looked up at her, puzzled. “Police work isn’t about passion. It isn’t about people being worried. It’s about doing what is good – what is useful – efficient. It’s up to us to decide what’s best for this community. Which cases warrant our involvement, and which do not.”

“Well, I guess we should just throw it away, then,” said Hella. “The letter, I mean. Destroy the evidence. Because if there really has been a crime, and we’ve been told about it but haven’t solved it, it will ruin our hundred per cent record.”

Her boss shifted uncomfortably in his chair, and she knew she had made her point. For Chief Inspector Eklund, police work held little interest, but he had a passion for neatness and efficiency. Under his direction, the Ivalo police district currently boasted the best crime resolution rate in the country, and even if the crimes they solved consisted only of petty thefts at the timber factory and the odd case of a poisoned dog, it didn’t matter. Only the numbers mattered to him.

And now Eklund was hesitating, his plump hands playing with a paper clip, his pale blue eyes fixed on something just above her left shoulder.

“We can write back to Mrs Waltari, explaining that her concern has been noted but that at this time of the year the risk of the police being caught up in a snowfall is just too great. We can tell her we’ll return to our investigation, if there is an investigation, in May next year, when the snow starts to melt and … at least, there could be something tangible …”

His voice trailed off, but she understood exactly what he was getting at.

“And if there is a body, we just find it when the spring comes?” she snapped. “Really? That is, unless that body has been eaten by wolves or bears, in which case we can still carry on pretending there was no crime?” Unable to stop,

she added, rather viciously: “Is that your golden standard of police work? Just ignoring cases when the weather conditions are too harsh?”

She had gone too far. Even a placid man like Lennart Eklund couldn’t take it any longer. She half expected him to throw her out of his office, or lecture her on the virtues of subordination, but what he said hit her far harder.

“Why are you pushing this, my dear? You’re a woman. You can’t go out there alone, can you? And both Inspector Ranta and I are very busy right now. Take my advice, forget about it. I’m not talking to you as your superior, but as an older, wiser friend. There’s that ball next week everyone is talking about. Put on a dress if you have one, and go. Or you can borrow a shawl and some make-up from Esmeralda. Her dresses would probably be a bit large in the chest for you, but I’m sure we could find you something …” He paused, thinking, his gaze summing up her body. “Kukoyakka from the timber factory seems to quite like you. Maybe he just has a thing for women who are” – Eklund hesitated, in search of a word that would describe her best, then brightened as he found it – “angular.”

......