Catholic Herald

Dorment, former art critic of the Daily Telegraph for thirty years, has selected over 100 of his reviews for this lavishly illustrated book. Ranging over the whole spectrum of art, from ancient and non-European to twentieth-century British and American, the author shows his catholic and eclectic tastes, his prejudices and passions. Full of information about artists, art movements and insights into particular paintings, alongside stimulating reflections on a large number of art exhibitions over the years, successful or otherwise, Dorment is always engaging and worth reading, whether one agrees with his opinions or not.

Art Quarterly

The Reviewer reviewed

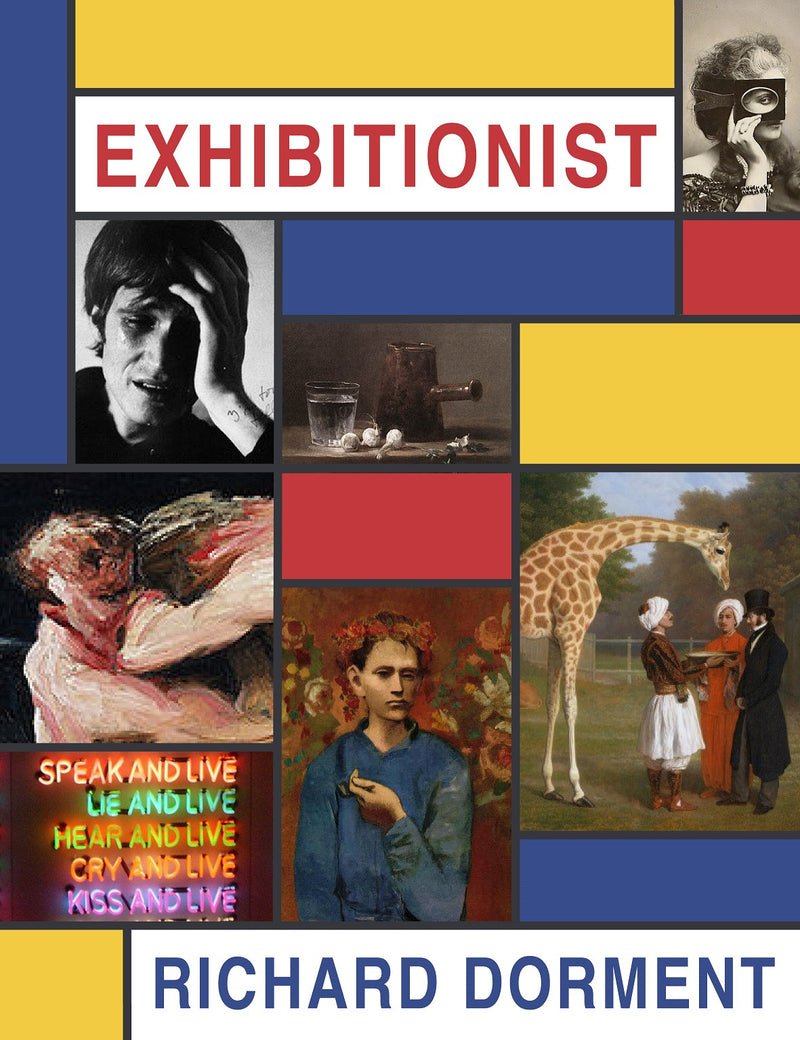

You would think nothing could be staler than old reviews, but this beautifully designed and illustrated book, which brings together a selection of more than 100 forthright, scholarly, bold, vivid and fascinating critical essays by Richard Dorment, is riveting.

Its appeal is twofold. Dorment who has extensive art-history and curatorial credentials and spent 30 years as the art critic of The Daily Telegraph, never disguises his personal individual reaction. (At “Egypt’s Dazzling Sun” at the Grand Palais in Paris (1993), he is so overwhelmed by the beauty of a particular portrait that he wants to kiss it, and explains why.) But the substantial foundations of his persuasive opinions are clear. And then there is the sheer verve of the writing, however contentious or pugnacious. His description of Tate’s sublimely beautiful and subtly hilarious “Swagger Portrait” show (1992) is typical. The Tate, we are told, managed to miss the point entirely: “Not just any grand full-length portrait can aspire to the status of Swagger. The true Swagger is a society portrait in which the artist substitutes sheer visual panache for the revelation of character. The purpose…pure, undiluted exhibitionism. The Swagger has all the subtlety of an oncoming bus”. “Vases and Volcanoes”, the exhibition about Sir William Hamilton (British Museum 1996) is the BM’s first sex-and –shopping show, he suggests, the mistress Emma Hart, who once posed nude as the Goddess of Health in a show at the Adelphi, and the results of Hamilton’s over-the-top shopping now a significant addition to the BM collections, from the Greek vases, bronze and cameos inter alias. And there is the authentic voice of The Exhibitionist of the book’s title. Read and enjoy: if you have seen some of these exhibitions, here is an extra helping. If you haven’t, here is an informative glimpse of what has been in Britain and occasionally abroad during a period of astonishing changes in the international art world, and the British art scene in particular. I defy even the experts not to learn something new.

Marina Vaisey, Art Quarterly Summer 2016

Spectator

The art critic who loved to provoke the Establishment

Richard Dorment doesn’t do whimsy. Or Stanley Spencer. He’s a fan of Cy Twombly and Brice Marden, Gilbert and George and Mark Wallinger, Rachel Whiteread and Susan Hiller. He loves writing about contemporary art. And he worked as art critic of the Daily Telegraphfor 25 years. Like the grit in the oyster he irritated the establishment, producing pearl after pearl that occasionally had even his own paper distancing itself from his opinions. ‘I looked edgy and transgressive,’ he says, ‘when in reality my taste in art was fairly cautious.’

Born in America, Dorment studied art history at Princeton and was assistant curator in European painting at the Philadelphia Museum of Art before moving to London and working as an exhibition organiser and writer on art. Having railed against the poor standard of art criticism in the British press, he joined the Telegraph in 1986, in good time to take a position in the furore that erupted over developments in contemporary British art through the late Eighties and Nineties, the years of Britart, the Turner Prize and the Saatchi Gallery.

Public opinion raged against these explorations of the boundaries and meaning of art, egged on by commentators who tossed all innovative art into one bag and dumped it as rubbish. By contrast, Dorment, and perhaps it should be stressed that he was not alone in this, engaged with what these individual artists, collectors and curators were doing and wrote about it in the same clear, intelligent prose with which he reviewed all the exhibitions he visited, from Ice Age Art to Fairy Paintings, from Caravaggio, Picasso and Pollock to Eygptian tomb paintings, video installations and performance art.

The selection of reviews in Exhibitionist, according to Dorment, includes those that make him look good, that read well and that say something new about the subject. Pace the slight whiff of self-congratulation, it’s hard to disagree. His enthusiasm (and in only seven of the 116 reviews is he not enthusiastic) is channelled into lucid descriptions, informative examinations of technique and speculative musings. For instance, in discussing the National Gallery’s exhibition on Turner’s ‘The Fighting Temeraire’, a painting exhaustively analysed, discussed and loved, seen as a symbol of a passing age, Dorment also draws a parallel with Turner’s own ageing and takes this thought one step further:

I looked again at the picture, and saw something I had not seen before: that there is a mythic quality about ‘The Fighting Temeraire’, with the black tug acting the role of the boatman Charon ferrying his ghostly galleon across the River Styx.

A book of collected reviews of art exhibitions is a curious thing. Shorn of their original purpose — to encourage the reader to go and look at something happening now — and removed from the medium in which the reviews originally appeared, concentrated in time rather than spread out over some 25 years, their impact and function have become something quite different. What could seem an exercise in vanity (the title offers a hostage to fortune) has become a testament to a critic of consistent integrity and openness. He reacts viscerally to beauty, to raw emotion (Bas Jan Ader), to intimations of mortality (On Kawara). He loves to winkle out a narrative (Caillebotte), he laments the stifling of symbolism in British art and he salutes genius wherever he finds it. He applauds academic rigour and excoriates intellectual sloppiness. The selection of reviews has also thrown up unintended resonances across the years: in 2002 Dorment wrote about Andy Goldsworthy’s ‘Moonlit Path’ made in the grounds of Petworth House in Sussex. Ten years later he reviewed an exhibition on Symbolist landscape in Europe and illustrated it with Prince Eugen’s painting ‘The Forest’ (1892). The two works make an extraordinary duo.

For those readers who, like me, have missed seeing many of these exhibitions, this book will be a welcome substitute. Of course more illustrations would have been a bonus, but this is, after all, the age of Google. The feel of the book itself is more like an exhibition catalogue than anything else, its design and layout elegant and sumptuous; and so I imagine it must have been annoying for all concerned that one of the full page plates is repeated in error.

Having worked as an exhibition curator himself, Dorment is scrupulous, and unusual, in crediting by name the organisers and designers of exhibitions. This is not to say that he pulls his punches when he doesn’t approve. The other side of his generosity as a critic is naming and shaming where he felt it necessary and there are a handful of reviews at the end of the book that must have made some people want to run and hide.

Oldie

I’ll start by declaring two interests: first, that I have known Richard Dorment for a decade; and second that, like him, I was the art critic of a national newspaper. Dorment, now seventy, is from the generation before mine. Even so, in our years at the Daily Telegraph and Independent on Sunday, we saw the world change side-by-side.

Recently, a famous New York dealer was asked what kind of work sold. His answer was immediate: ‘Stuff that looks good on the screen.’ The people who bought six- (or seven-, or eight-) figure works from him were too busy making money to visit galleries. They collected off laptops. And as with art, so with art criticism. Dorment has been replaced on his paper by a critic half his age and very much more telegenic – indeed, who is better known as a television critic. In March, the Independent on Sunday went online. Before that, it had fired all its critics on the grounds that – laughably, given what the Russian-owned paper paid – they were too expensive. Actually, they were expendable because the skills for which they had been hired – knowledge, experience, good grammar – had come to seem worthless. In the generation after Dorment’s and mine, art critics will speak to their audiences, not write to them; on-screen images will discuss images on-screen. I suspect Richard Dorment is glad to be out of it.

This is a change less of age than of taste. Post-war art history held that an artist’s life must not intrude on his work. The opposite has been true of art criticism. Critics with obtrusive personalities – who wave their arms, speak bad Italian and wear black buttoned over their stomachs – are critics who do well on TV. Richard Dorment would never have been one of these. This collection of his reviews is called Exhibitionist because he is not. His criticism dates from a day when chefs stayed in kitchens and embarrassing bodies in doctors’ surgeries. If, like me, you have not been a Telegraph reader, then it takes time to get used to this reticence in Dorment’s writing. Where are the tics we expect in modern criticism? The splutterings and winks? Not in Exhibitionist: Dorment’s style is styleless, and stylishly so. His chosen place is next to the reader, not in front of him. If you set out to deduce Richard Dorment from this book, you might end up with a mannerly Princetonian in a rumpled jacket, which would not be far from the truth.

There are more than a hundred reviews in Exhibitionist, dating from the mid-1980s to last year, of work ranging from the Ice Age to the YBAs, Downtown LA to the Valley of the Kings. Not wanting to get between you and their author, I will choose two at random. The first is of a one-picture show, of Turner’s ‘Fighting Temeraire’. It is a work we all think we know – which Dorment thought he knew. His review begins: ‘Yet another illusion shattered!’ Turner never saw the Temeraire: the nearest he came to it was an account of her end in the Times. Wistfully, the Telegraph’s ex-critic admits to his disappointment at this, embarrassment at his own gullibility; then he deftly reinvents Turner’s canvas as a tour de force of the Victorian imagination rather than a great history painting. Freed by this revelation, he looks again at the work and ‘sees something [he] had not seen before’, the black steam tug as ‘Charon ferrying his ghostly galleon across the Styx’. It is beautiful criticism.

The second review is of a small exhibition in Leeds celebrating Herbert Read’s centenary. Dorment was prone to review unfashionable shows: although he cursed the conservatism of the Telegraph, it was this that allowed him to do so. His estimation of Read as a critic (good, but not so good as Douglas Cooper) is customarily even-handed. Then he adds a line that might stand as an epigraph for this book, or himself. ‘The more successful an art critic is at his job,’ Dorment writes, ‘the harder it is for subsequent generations to understand why.’ A generation from now, people may read Exhibitionist and not see its point. It is a nasty thought.

Turnaround: May books we loved

I’ll be the first to admit that I am a massive geek for all things art historical. So I jumped at the chance to write about Exhibitionist, which despite the racy-sounding title, is a really great collection of essays by one of the best art critics around. Importantly to any art nerd, there are loads of full-colour, full-page reproductions and illustrations throughout.

Richard Dorment was the art critic for the Daily Telegraph from 1985 until his retirement last year. Over these 30 years, he was to become one of Britain’s most influential art critics, assessing and documenting the contemporary art and exhibition scenes in a time of remarkable change. The book opens with a fascinating introduction where Dorment recounts his impressive career. His first brush with art history came as a classics student at Princeton University, when he sat in on a lecture about Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. Overcome with enthusiasm, he swapped majors straight away. This passion for his subject shines through all the reviews in this collection and is what makes them such engaging reads. Dorment then worked as a curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art for ten years before moving to London and taking up his position at theTelegraph. Writing almost every week, it was his job to introduce, explain and criticise the most significant current art exhibitions for a popular newspaper audience.

For this collection of essays Dorment has selected 106 reviews from over 1,000 he published during this time. While it obviously has a focus on contemporary art, there is a wonderful breadth of subjects covered, with the essays divided into sections by era. Starting with a review of Ice Age Art at the British Museum, the book takes in nearly all the significant art up to the present day, making for an astonishingly readable and accessible introduction to the work of the world’s finest artists.

Rather than a standard retrospective, the essays form a collection of contemporary informed reaction to the major exhibitions of the time, ranging across London, the rest of the UK, Paris, Amsterdam, New York and Washington. Big names like Miró, Magritte and Lichenstein are included alongside more obscure artists – Belgian video artistFrancis Alÿs, nineteenth-century photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, and Danish Romantic Christian Købke. What’s interesting is not just his appraisals of the artworks themselves, but also how museums and galleries have displayed them throughout the years.

During his career, Dorment became one of the driving forces of increased acceptance of modern art by the British public. While the Young British Artists (YBAs) – including Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin – were ripped to shreds by the mainstream press, Dorment took their art seriously. Despite seeing himself as quite conservative in his tastes, he was often controversial. In his early days at the Telegraph, his opinions would sometimes provoke the editors to run leaders the next day distancing the paper from his latest review. But it was his fellow critics in the popular press who Dorment saw as the real enemy of contemporary art. Often they too refused to accept the new and reached for lazy clichés before analysis. He once wrote that “had the same critics been writing about film, sport, or the stock market they’d have been rumbled in a week.”

While to many his reviews were seen as just another example of art-world elitism, they are in fact completely accessible and never condescending. The writing throughout this collection is a refreshing antidote to so much art criticism today, where art-babble is regurgitated from press releases without any serious analysis or reflection. Dorment is thankfully light on both purple prose and dense theoretical digressions. He is careful to approach each artwork, whether an Impressionist canvas or brash neon lettering, on its own terms. One of my favourite essays in Exhibitionism is the beautiful review of Olafur Eliasson’s 2003 installation in the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, The Weather Project,which demonstrates his gift for assessing art on an emotional level:

“When I first saw The Weather Project, I thought of the sun rising through vapour in one of J M W Turner’s landscapes. But, late on a Saturday or Sunday afternoon, when hundreds of people stand mesmerised in the face of the glowing disc, the work becomes truly frightening, a modern interpretation of one of John Martin’s or Francis Danby’s apocalyptic visions of the end of the world. A close encounter of the third kind.”

Dorment was never afraid to say when he disliked an exhibition. High-spirited and hard-hitting, at one point he calls a David Hockney painting “repellently slick and superficial”, while a Renoir is “so slapdash in its execution that the surface looks like a bar of soap that’s melted in the bath” (an early follower of #RenoirSucksAtPainting, maybe). It’s almost a shame that he hasn’t included some of his famously acerbic one-star reviews, such as 2015’s Sculpture Victorious at the Tate Britain, which he called “so cack-handed it’s depressing”. However, as he explains, he always preferred to write about what he did like. And what he did like, luckily for us, encompasses some of the finest and most memorable cultural events of the last three decades. Provocative and open minded, but always essentially explanatory and helpful in its approach, the book is compulsively readable – highly recommended for enthusiasts and art newbies alike.