'Like The Vampire Of Ropraz, Jacques Chessex's previous novel (see my review here) published in English translation by Bitter Lemon Press, A Jew Must Die is based on an historical crime, and like the first book it raised questions Swiss society did not necessarily want raised. But where Vampire was more concerned with the way society reacted to a crime, A Jew Must Die is more concerned first with the crime itself, the murder, in Payerne, of a Jewish cattle-merchant by Swiss Nazis, and by the lack of reaction from Swiss society to this crime. The beauty of the work, if beauty is the right word, is the way Chessex expands that lack of reaction into a wider indictment, an analysis using the Swiss microcosm of the awful phenomenon that was the Third Reich.

He does this in prose that is consciously bare, factual, its emotions controlled. Chessex grew up in the area where the murder took place; he was at school with the son of one of the killers, and there is something very Swiss about the cold rationality with which he presents his story. It is a tone which survives the translation by W. Donald Wilson, and since Wilson translated Vampire as well it is telling that he's able to convey Chessex's different voices so well.

There is also a fairy-tale, brothers Grimm feel to the story, particularly as the gang of ne'er do wells who make up the local Nazi party try to lure Arthur Bloch to his death on the pretext of buying a cow, and one for which he appears to offer them a good deal. That they then butcher Bloch as they would an animal only heightens the monstrosity of the crime, but it is the relative lack of reaction from the locals which makes clear the parallel with the larger monstrosity that was the Holocaust, and the way the good burghers of Austria, Germany and more countries conspired with their silence and indifference to help it happen.

In the character of Fernand Ischi, the local gauleiter, Chessex both sets him apart and fits him into his community. Swiss authorities handed out severe sentences to the murderers, but the reaction of the locals was to ignore it, as if it had never happened. Yet when Chessex moves to the present, and himself, he discovers that in some ways nothing has changed in his small world.

Arthur Bloch's tombstone read Gott Weiss Warum. God Knows Why. It is a telling and perfect amibiguity that lies at the heart, just beneath the perfect surface, of this novella. Chessex died last October, my obituary was published in the Guardian two months later, you can link to that here, and to my IT posting here. The Last Skull Of M. DeSade, his last novel, is scheduled to appear from Bitter Lemon next year.' - Crime Time II

'This short novel is one of the most powerful accounts of the horrors of anti-Semitism as it descended into mass Jew-killing. It is set not in a Nazi death camp but in peaceful, neutral Switzerland. The Swiss asked the Germans to put the infamous "J " for Jude (Jew) on the front of German passports so that Swiss frontier guards could know who were German tourists and who might be Jewish asylum-seekers. In the 1930s Davos was home to the biggest section of the Nazi party outside Germany.

The Goncourt prize¬winner Jacques Chessex is one of the best-known Swiss novelists writing in French. The story is a true one. He grew up in the small French-Swiss town of Payerne. There, a group of xenophobic Swiss, egged on by a Jew-hating pastor, Philippe Lugrin, decided to anticipate the final victory of Nazism by killing a Jew just before Hitler's birthday in April 1942. They chose a cattle dealer, Arthur Bloch, who came from Berne to the Payerne cattle market. The killing was sadistic and prompted by Bloch's Jewishness and nothing else.

Well-translated by W Donald Wilson, the prose is taut, verbs and nouns in short bare sentences driving the story forward to its gruesome end. Chessex went to school with the children of the killers and met Pastor Lugrin by chance in Lausanne in the 1960s where the priest was still ranting about Jews.

Bloch's grave stone carries the inscription Gott weiss warum: God knows why. This is Chessex's only concession to the familiar trope of Holocaust literature: why a Jewish or Christian deity allowed it to happen. In fact, politics allowed it to happen...' - Financial Times

'IT'S 1942, a few days before Hitler's birthday and a group of Nazi sympathisers in a small Swiss town decide to murder a local Jew - for no real reason other than that they can. They lure him into a stable, bash him over the head with an iron bar, then cut up his body and dump it in a lake. A Jew Must Die (£6.99, Bitter Lemon) is another novella from the pen of Jacques Chessex, one of Switzerland's greatest writers. It may be a novel, but it is also a true story, and Chessex should know - as a child, he knew the killers and sat next to the children of one of them at school. Like The Vampire of Ropraz, also available from Bitter Lemon, the book brilliantly evokes the evil of the central deed - all the more horrific in that it really happened - while seeing, with a poet's eye, the beauty of the surrounding countryside. Chessex writes sparingly, the book is just 92 pages and can be read in one sitting. Much of it is written in the present tense, making the nightmarish incident all the more immediate. Europe is in flames and Switzerland, while not directly involved in the war, is suffering from high unemployment. The rural market town of Payerne suffers a number of bankruptcies, the locals are out of work and money, and looking for someone to blame. Fernand Ischi, leader of the local Nazi cell, blames everything on the Jews and the murder is to be an example, a foretaste of what is to come once the Nazis take over Switzerland. He figures the killing will put him in favour with Hitler's men when they arrive and he will get an important post in the local Third Reich regime.' - Newham Recorder

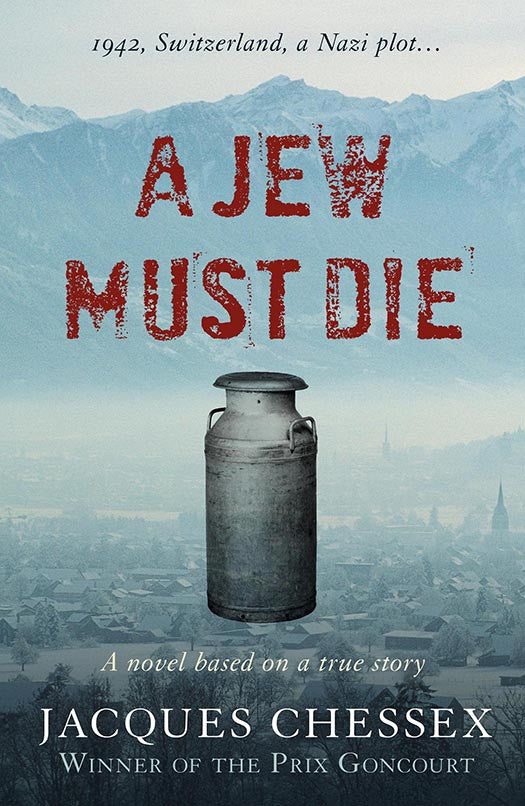

'Told in spare and sober prose, Prix Goncourt-winner Chessex's final novel, based on a true story, is a masterpiece. Set in 1942, in the picture-postcard Swiss town of Payerne, it's an account of how the local Nazi cell set out to murder a Jewish man in order, in the words of their leader, "to set an example for Switzerland and for the Jewish parasites on its soil". The chosen victim, local cattle merchant Arthur Bloch, is bludgeoned to death with an iron bar. He is then dismembered, the body parts being stuffed into milk churns and sunk in Lake Neuchâtel, where they soon resurface. There are no plot twists here and no sensationalism either, just a harrowing and thought-provoking picture of fear and prejudice that will stay with you long after you finish this small but intensely powerful book.' - Guardian

'Those interested in Nazi activity in neutral Switzerland during WWII will best appreciate this slight novella from Prix Goncourt winner Chessex (The Vampire of Ropraz). In April 1942, in the small market town of Payerne, an anti-Semitic pastor incites a band of local Nazis "to set an example for Switzerland and for the Jewish parasites on its soil. " National Movement leader Fernand Ischi and his thugs target a representative Jew, cattle dealer Arthur Bloch, whose murder will make a fine birthday present for Adolf Hitler. While this book generated controversy in Switzerland, where the country's role in WWII is still a sensitive issue, U.S. readers will find that it falls short of, say, Jerzy Kosinski's The Painted Bird and other works that view the Holocaust through isolated instances of violence. Chessex (1934-2009), who was born in Payerne, was also an essayist, poet, and painter.' - Publishers Weekly

'If you're looking to surprise book lovers on your gift list, you can't do better than giving them two paperback thrillers by Jacques Chessex.

Never heard of him? Join the club. The American club, that is.

Chessex, who died last year, was celebrated in Switzerland and France, winner of many prizes and the first non-French author to win the the Prix Goncourt. But things like that usually mean zip in the United States because we don't tend to read books in translation (Stieg Larsson aside). Currently, only about 3 percent of our books are translated from other languages. In Europe, it's more like 30 percent.

Chessex's two short thrillers available in English are so gripping it's hard to believe they were written in any language but English. The prose is taut and tense; the stories are knock-outs. Chessex lived in northwest Switzerland which is where both novellas are set. It's a bleak, unforgiving region he compares to the Carpathians.

A Jew Must Die takes place in 1942 close to Hitler's birthday, when most of Europe has been subjugated by the Nazis and the Soviet Union seems bound to fall next. A vicious Minister and a megalomaniacal Swiss Nazi want to rouse the Swiss people and offer Hitler a perverse birthday present: a dead Jew. They want this act to guarantee them power and a prominent place in the New Europe when Switzerland becomes part of The Reich. Their target? A prominent well-liked cattle merchant. How he dies, how they hide the body, and the initial response to the man's disappearance will shock you.

The Vampire of Ropraz isn't sleek and elegant: he's a brain-addled fiend who violates the corpses of beautiful girls in bestial ways. Set in 1905, it's a story of insanity, suspicion and profound ignorance. The countryside goes wild with panic and the crimes feel like all the "dreaded secrets of an evil world" have been set loose. Neither one of these novels could have endeared Chessex to his neighbors; they paint the Swiss of the region as superstitious, venal, and backward, steeped in cruelty.

At only around 100 pages, both thrillers pack more power than books many times their length, and raise profound questions about complicity and guilt. Even more striking, Chessex knew the Jew-killers he fashioned the first novel about, and his vampire novel is based on a true story.

At one point Chessex invokes Baudelaire's "To the Reader," implicating himself and his readers in "Folly, depravity, greed, mortal sin." You realize then that you've been reading much more than a thriller, and a different kind of chill settles in.'

- Huffington Post

'Swiss writer Jacques Chessex was haunted all his life about a horrific anti-Semitic murder that took place in his town of Payerne in 1942. A Jew Must Die is the stunning novella he wrote about it, and it packs more power in its ninety-two pages than many novels four or five times its length.The book is set before Stalingrad, when Europe still lies at Hitler's feet. His string of victories has emboldened Swiss Nazis. They hold torchlight meetings, bellow Nazi propaganda about a New Europe, dress like their heroes, and threaten the Jews of Switzerland with every kind of punishment. Peaceful little Payerne in northwest Switzerland is not immune to this agitation. Not far from Dijon in France and Freiburg in Germany, it's become the stomping ground of a militantly Jew-hating Minister whose words bear fruit in a town with massive unemployment:

In these remote countrysides the hatred of the Jew has a taste of soil mulled over in bitterness, turned over and ruminated, with the glister of pig's blood and the isolated cemeteries from where the bones of the dead still speak of misappropriated inheritances, suicides, bankruptcies, and embittered, frustrated bodies a hundred times humiliated. Hearts and groins have oozed a heavy broth into the black, age-old earth, mingling their thick humours in the opaque soil with the blood of herds of swine and horned cattle. The mind, or what remains of it, inflamed by murky family and political jealousies, is looking for a scapegoat to blame for all life's injustice and suffering, and finds it in the Jew. The hatred co-exists with the beauties of the landscape and the quotidian reality of cattle herding and farming, which makes it even more terrible when the well-known Jewish cattle merchant Arthur Block is singled out for slaughter. Led by a local Nazi with delusions of grandeur, the murder is meant to be a gift to Hitler for his upcoming birthday, and a down payment on Switzerland's entrance into the Reich.

The greatest twist in this terrible, mesmerizing story is when the author appears and tells us of his conflicted engagement with the tale he cannot help but telling. It's a masterful turn in an extraordinary book whose last pages are on fire. No wonder Chessex won the Prix Goncourt and so many other awards in his long career.' - BiblioBuffet

'I was with friends; they asked what I was reviewing. Unthinkingly, I pulled out Jacques Chessex's novel A Jew Must Die and showed them the cover. The look of sheer horror on their faces told me this was a mistake. "It's an anti-Nazi book, " I assured them. They knew that already -- they're my friends, after all, and they're fully aware I'm not a closet skinhead. But the title still disgusted them. One of them even told me to make sure not to take it out of my bag on the subway (I didn't). I don't blame them for being put off, though; the title made me uneasy too. That seems to be the point. This is a blunt book, with little concern for the reader's comfort. In less than 100 pages, Chessex takes us through each stage of the murder of a Jewish businessman named Arthur Bloch. It is 1942, and a group of Nazi sympathizers in Payerne, Switzerland, intend the killing as "birthday gift " for Hitler -- who they're convinced will reward them when Germany inevitably invades. Nearly every sentence is dedicated to the facts of the case -- who inspired it, who planned it, and what they did to execute it. We meet a viciously anti-Semitic former pastor, Philippe Lugrin, who inspires the plot, boasting of his connections to the Nazi party. And we see a local derelict, Fernand Ischi, assemble a team to carry it out. But they never become fully fleshed out characters; we hear only of the murder, and how they contributed to it. Even the triggerman -- a hapless lackey named Ballote -- registers as little more than a name.

The author wants us to focus on the act itself. His narrative voice is often clinical and detached. Details are kept spare. Bloch's death is described in the most stripped-down language imaginable: "The forehead is pale, shining with sweat. A moan, accompanied by rattles in his throat. Ballote fires. Bloch's body collapses to the ground. A trickle of blood comes from his mouth. "

As a native of Switzerland -- the book was first published in French last year -- Chessex's interest in the story is obvious. Though officially neutral in the Second World War, Switzerland saw its share of pro-Nazi activity during the 1940s. In fact, A Jew Must Die is inspired by real events. It is hard not to see the book as, at least on some level, an interrogation of Swiss anti-Semitism. One of the book's most striking passages concerns not the perpetrators, but the people of Payerne, who respond to Bloch's disappearance with indifference: "And even those who would denounce Fernand Ischi and his gang at the trial still mock the Jews and their age-old terrors. A cattle-dealer has disappeared? An interesting turning of the tables: that's what people think in Payerne. " What keeps this from being merely a Swiss concern, however, is the way Chessex uses subtle shifts in voice to shape the reader's experience. At times the narrator seems almost omniscient, filling us in on Bloch's business contacts in Payerne or Ischi's taste for violent sex. At other times, he exhibits a palpable disgust with the culprits, calling Lugrin "perverted. " And on several occasion, he seems to speak for the murderers themselves, such as when he declares "We mustn't get caught. " This is a very delicate experiment -- and a largely successful one. It gives Chessex a great deal of control over his readers' emotional response to the story.

At one point, the narrator even speaks on the reader's behalf. It all starts when he describes Ischi as an "apprentice Nazi Gauleiter " (party official). Suddenly, the narrator is interrupted -- "'Gauleiter?' you say. 'Isn't that going a bit fast?' " The key is Chessex's use of the word "you " -- he is addressing the reader, and implying "you " are defending a Nazi. Throughout, the narrator returns to this subtly accusing tone. The reader is not an audience but an accomplice. It is not only the Swiss who are meant to examine their consciences. A Jew Must Die pushes readers to question their own moral culpability -- no small achievement. It is not a perfect book -- its narrow focus means it is ultimately not as definitive as, say, Elie Wiesel's Night or Primo Levi's If This Is a Man. And the book's cold, almost remote tone will put off many. But by subtly widening the blame for the Nazis' crimes to an entire culture -- whether that means Payerne, Switzerland, Europe, or all of humanity -- Chessex reminds us the Holocaust is a living concern, as opposed to something that is only the responsibility of thugs from the distant past.' - New Jersey Jewish News

'A novel more frightening because it is based on a true story, Chessex's chilling tale set in the early 1940s portraits the brutal murder of a Jewish businessman. As the inhabitants of a small Swiss town face economic hardship and the uncertainty of war, a handful of Nazis supporters fan the flames of hatred and hatch a token murder. At first, townspeople view the disappearance of Arthur Bloch with mild interest but when body parts begin appearing they are forced to face the fact that members of their community have perpetrated a heinous crime.

Spare prose and a taut writing style carry this horror story while conveying the feel of living in an isolated mountain community during turbulent times. The economic hardships faced then eerily parallel the challenges faces by society today and provide a grim if timely reminder of what can happen when normally decent people seek a scapegoat.' - Monsters and Critics

'A Jew Must Die -- as the stronger English title has it (the French original has it as a Jew being made an example of) -- is a very slim work that is as much documentary as fiction. Chessex was born in Payerne in Switzerland -- the small-town setting of the episode --, and he was eight years old when the events he describes took place in 1942; his classmates were the sons and daughters of some of the principals in the story. Chessex is moved to write the story because when he was a child it was clear that: Arthur Bloch is not spoken of. Arthur Bloch, that was before. An old story. A dead story.

But the adult Chessex recognizes that not that much has changed, and that this is an incident -- like too many others -- that was never properly dealt with. Chessex describes early 1940s Payerne, where there are characters that believe a Nazi takeover is imminent and desirable. Overall, the war is far off, but times are difficult and many have suffered. Here, as elsewhere, Jews are convenient scapegoats:

In these remote countrysides the hatred of the Jews has a taste of soil mulled over in bitterness, turned over and ruminated, with the glister of pig's blood and the isolated cemeteries from where the bones of the dead still speak, of misappropriated inheritances, suicides, bankruptcies and embittered, frustrated bodies a hundred times humiliated.

Those responsible in town for maintaining order turn a blind eye towards the hate-mongering:

They'd rather cut out their tongues, rupture their eyes and ears, than admit that they know what is being plotted in the garage. In the back rooms of certain cafés. In the woods. At Pastor Lugrin's. What the local Nazi wannabes decide is that:

The time is ripe for the band to set an example for Switzerland and for the Jewish parasites on its soil. So a really representative Jew must be chosen without delay, one highly guilty of filthy Jewishness, and disposed of in spectacular manner. Threats and warnings. A good house-cleaning. Purification. A means to hasten the final solution. Sieg heil !

Berne cattle-dealer Arthur Bloch fits the bill. And he's due in town later in the month, to attend a livestock fair. And so he is made an example of. Bloch is a decent, successful man; what happens to him is almost ridiculous in its savagery and ineptness. The thugs that attack him -- and the puppetmasters that orchestrate the crime -- are caught up in such blinding hatred that they can't see the pointlessness of their actions. Needless to say, it neither helps their pathetic cause nor serves as any sort of example -- except to demonstrate how easily poisonous thoughts can take hold even in what is considered a safe and civil society. Years later Chessex encounters ideological ringleader Pastor Lugrin: the church-man is unrepentant, even after serving some fourteen years in prison, coming out: "more ardent than ever, virulent in the density of his hatred " (and telling Chessex that his only regret is: "that I didn't bring others to my friends' attention", i.e. that just the one Jew was made an example of). Chessex describes what happened, what led up to it, and then the aftermath in relatively quick and simple terms. He does have a tendency to wax lyrical at times: this is not the straightforward prose favored by most Holocaust authors, as, for example, he writes:

But evil is astir. A powerful poison is seeping in. O Germany, the abominable Hitler's Reich ! O Nibelungen, Wotan, Valkyries, brilliant, headstrong Friedrich .

Yet he pulls back when need be -- and, most effectively, steps to the fore when the time comes:

I am telling a loathsome story, and feel ashamed to write a word of it. I feel ashamed to report what was said: words, a tone of voice, deeds that are not mine but that I make mine, like it or not, when I write.

But he recognizes the need for speaking out, for writing about it -- despite (or: especially because of) the deep-rooted shame which still has hold over Payerne. And, though it goes unmentioned, and though the focus is only on this single act of terrible, pure evil, it obviously is meant to be a reminder that all claims of tolerance and functioning social order rest on very shaky foundations. The hatred and irrationality described in this book are not that far removed from what led to Switzerland's recent vote banning minarets, or similarly intolerant behavior and attitudes found all across the world. Civil society, Chessex suggests, is separated from barbarism by only the smallest of distances -- and not confronting it, immediately and forcefully, when it is first glimpsed makes us all complicit in the spread of barbarism.

A powerful, small work.' - The Complete Review

'Haunting. Disturbing. Very nearly true. A Jew Must Die, by Jacques Chessex, is a fictionalized account of the horrific murder of Arthur Bloch, a Jewish livestock dealer in the Swiss village of Payerne.

When Bloch is coaxed from Market Square to a quiet shed, he does not suspect that he has been selected for slaughter much as he selects animals for butchering. Bloch is well known, successful, and a devout Jew. The Nazis in Payerne have been urged to make an example of just such a person by the inflammatory diatribes of the Reverend Lugrin, a cold-blooded instigator. The murderers intend Bloch's death to be a birthday tribute to Hitler. The reaction of Payerne's citizens is as disturbing as the method his killers use to dispose of Bloch's remains. The townspeople react to the disappearance of this well-liked individual with "sniggering, coarse jokes, and loaded comments. "

The straightforward narrative style of A Jew Must Die contributes to its powerful effect. The facts do not need much elaboration. Readers familiar with Elie Wiesel's Night will recognize the drama of individual experience in the shadow of global events. Personal experience can be more revealing than a volume of statistics in understanding the social history of the 1930s and 1940s. Readers who hope to understand that time and glimpse the darkness of the human heart will find this brief book worthwhile. Translator W. Donald Wilson has accomplished a natural-sounding English translation from the French.

Jacques Chessex was eight years old, living in Payerne, Switzerland, in 1942, at the time of the real events that underlie this story. His father, the president of a local anti-Nazi club, was on the list of future victims compiled by Fernand Ischi, leader of the "garage gang " responsible for Arthur Bloch's murder.

Mr. Chessex, who died in October 2009 at age seventy-five, was a poet, essayist, and painter as well as a novelist. He was the first non-French citizen to receive the prestigious Prix Goncourt for his novel, L'Ogre. In 2007 he was awarded the Prix Jean Giorno for his life's work. According to the obituary published in London's Guardian, his work focused on "revealing the darkly uncomfortable truths beneath the pristine surface of Swiss society. " A Jew Must Die does just that.'

- ForeWord Reviews

'Based on a real event in 1942, this is a novella of immense power. Jacques Chessex, who died last year, was preoccupied by problems of evil. At school in the tiny Swiss town of Payerne, he sat next to the daughter of a Nazi murderer who, with several accomplices, killed a Jewish merchant who came to their town to buy cattle. They lured him to a byre, felled him, cut up his body and hid the pieces in milk cans which they sunk in Lake Neuchâtel.

The language in which Chessex describes this is pared to an absolute minimum of sensationalism. Yet his descriptions are so close and precise that the contrast between the human butchers and the rich kindness of the natural world takes on a metaphysical intensity. How can we make sense of such a world, and who is to blame?

When this book was first published, the people of Payerne were apparently offended at this record of a crime perpetrated in their midst. They need not have felt unjustly singled out, for Chessex makes the murder of a single Jew a parable of larger events. If it is true, as Edmund Burke suggested, that the only necessity for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing, then the folk of Payerne were no worse than those everywhere who had some complicity in the Holocaust.

Chessex has commented that the victim of our time is the Senegalese asylum-seeker. But in this, his last work, he grapples with the statement of the philosopher Jankélévitch, who declared the Holocaust 'imprescriptible'. This was formerly an archaic legality, used neutrally to mean concepts which could not be bound by legislation. Post-Jankélévitch, it has taken on fearsome meanings such as an act of absolute evil for which there is no redemption.

However, as Chessex interprets it, there are particular connotations for the writer, such as the possibility that the "imprescriptible" Holocaust cannot be written about: because it was of such magnitude in its horror that there is a moral complicity even in the fiction writer's imaginative participation in describing "deeds that are not mine, but that I make mine, like it or not, when I write". Is fiction about the Holocaust therefore an acquiescence?

Chessex's answer is to describe the martyrdom of a single individual and convey the monstrosity endured by a whole race. In its imagined evocation of historical fact, A Jew Must Die is in itself a justification of the power of art. This brief, disturbing masterpiece goes to the heart of the creative process.' - Independent

'The title is a shocker: A Jew Must Die. When the book first appeared in the mails, I thought that the small-scale paperback -- so different in shape and design than most books I usually receive -- might be some anti-Semitic tract, and that the title had been chosen to be purposefully scandalous, and to frighten and provoke. But the shock goes far deeper than that, and comes from the fact that this is fiction -- yet unlike any fiction about the Holocaust that I've ever read. The author is Jacques Chessex, hailed as one of Switzerland's finest writers, who won the Prix Goncourt -- France's most prestigious literary award -- for his 1973 novel L'ogre. A poet and essayist as well, he is also the winner of the French Literature Grand Prix of the Académie Française.

We are informed right at the start by the publisher, Bitter Lemon, out of London, that this is a novel based on a true story. The scene is Payerne, a small Swiss town, and the time is April 1942, several days before Hitler's birthday. A group of local Nazis has decided, as the title states, that a Jew must die. The death will be used as an example, to show the Swiss people that Nazism is bound to win-- that it is, in fact, on the verge of success everywhere, and that this "representative" murder will demonstrate what the future will bring to the nation and to all of Europe once Hitler triumphs.

These Swiss fascists have chosen their victim with the utmost care, to prove their point beyond dispute. Arthur Bloch is a cattle merchant, one of the area's "filthy rich" Jews, in these Nazis' opinion, and like the other Jews clogging Switzerland, he is supposedly responsible for the economic misfortunes that have plagued the country during the 1930s and beyond. (Most of these Nazis, as might be expected, are unemployed, with little else to do but sit around and hunt for scapegoats.) In these men's minds, the Jews are sucking dry the true blood of the Swiss people. They consider Arthur Bloch to be representative, and so worthy of death. What is most extraordinary about this book, aside from its unflinching depiction of hatred and its consequences, is that Chessex was a (non-Jewish) child in Payerne, and he knew the murderers, even sat next some of their children at school. I have read many memoirs about growing up Nazi or about discovering that one's parents were party members, but I don't think I have ever run across a work of Holocaust fiction that tries to imagine an actual event that the author had such close contact with. It gives the narrative, brief as it is, an extra charge. There is drama here and horror, as well as a sense of historical reckoning, which means looking collective guilt squarely in the eye.

Full Spectrum of Emotions

In a very small space -- the entire novel runs less than 100 pages -- Chessex manages to give us the full spectrum of emotions: humor, hatred, terror, pity, savagery all bound up in the story of this terrible murder of an innocent man. The author also manages, with swift strokes, to give us a wholly credible portrait of Nazis, and does it without a cliché in sight. Chessex describes the leader of the hate group in this way: "In Payerne, in the Ischi brothers' garage opposite the Town Hall and the cool, mysterious deer park, the youngest of the brothers, Fernand Ischi, has been a member of the Swiss National Movement for the past several years. In Georges Oltramare of Geneva, this Fernand had found a thundering leader of the extreme right, a great beguiler, crafty tactician, unscrupulous orator, provocateur and troublemaker. Oltramare has one obsessive design: the victory of Nazi Germany, and then the extermination of the Swiss Jews. In Geneva, Fernand Ischi, an unskilled helper in the family garage and occasional repairer of bicycles and motorcycles, a ne'er-do-well exiled from the town of his birth, has followed this Nazi kingpin Georges Oltramare from meeting to meeting and has fallen under his spell. ...

"From the age of 16, after leaving school, where he was an average student, inspired only by gym class, Fernand Ischi has been entranced by Germany, Hitler's seizure of power, the rise of Nazism and its violence. In 1936, during the Berlin Olympics, he saw Leni Riefenstahl's films in Geneva cinemas and developed a passion for the hard, clear propaganda ideal: the beauty of the Aryan physiques, the banners, the nudity, the blond hair, the fanfares of Gothic trumpets, the blue eyes gazing up into the Fuhrer's ecstatic gaze ... Fernand Ischi is a mass of yearning and solitude. The blinkered mentality of his native town."

Ischi and his followers meet and consider a number of possible victims before settling on the devout, well-to-do Bloch, from Berne, "well known to the farmers and butchers throughout the area, making him an obvious and exemplary victim." They will strike at the next livestock fair in Payerne, set for Thursday, April 16.

I will spare you any quotations from the grisly murder scene, which is done with extreme writerly care (in the sense of wishing to be faithful to the truth). This means that it's a stark and difficult read, but not one iota of it is meant to be sensationalistic. This is a murder examined in its terrible reality so that the writer can demonstrate fully how hatred and twisted ideas can lead to barbaric ends. Another astounding factor in Chessex's novel is what he transcribes after the deed has been done: a short chapter that sums up the matter of national guilt, of how a people consider a crime that indicts them all in some way. Then, even more shocking, the author steps in to consider the matter in the opening portion of the very next chapter.

'A Loathsome Story'

"What is horror?" he asks. "When the philosopher Jankélévitch proclaims the entire crime of the Holocaust to be 'imprescriptible,' he forbids me to speak of it exempt from that edict. Imprescriptible. That can never be forgiven. That can never be paid for. Nor forgotten. Nor benefit from any statute of limitations. No possible redemption of any kind. Absolute evil, for which there can be no absolution ever.

"I am telling a loathsome story, and feel ashamed to write a word of it. I feel ashamed to report what was said: words, a tone of voice, deeds that are not mine but that I make mine, like it or not, when I write. For Vladimir Jankélévitch also says that complicity is cunning and that repeating the slightest anti-Semitic sentiment or deriving some amusement or caricature from it, or putting it to some aesthetic purpose, is already, in itself, inadmissable. He is right. Yet it is not wrong of me, having been born in Payerne and spent my childhood there, to explore events that have never ceased to poison my memory and left me ever since with an irrational sense of sin.

"I was eight years old when these events took place. In high school I sat next to Fernand Ischi's eldest daughter. The son of the officer commanding the police station who arrested Ischi was a pupil in that same class. So was the son of Judge Caprez, who would preside over the trial of Arthur Bloch's murderers. My father was principal of the high school and the Payerne elementary schools; since Ballotte [one of the fascist gang] had been a pupil of his, he was interviewed as a witness during the preparations for the trial. He was President of the Cercle de la Reine Berthe, a democratic, violently anti-Nazi club, and was himself on the list of future victims of the garage gang ... ."

There are only 10 pages or so left to the book after this startling news is delivered, but they are filled with additional shocks and insights into a warped form of group mentality, and only add to the memorable -- though necessarily queasy -- quality that marks A Jew Must Die.'

- Jewish Exponent

'In a small rural town in Switzerland, people are usually more concerned about the quality of the cattle and other farm produce at the local market than they are about global affairs. But in 1942, such events cannot be ignored. Hitler's armies are ascendant, and his evil philosophy is designed to appeal to the ignorant, second-rate failures that inhabit every town or village in the world. Remember the school bully, dominant in his teens but condemned to a life of tedium at the bottom of the pile when entering the real world? This is the kind of person for whom Hitler's ideas of racial superiority appeal. And A JEW MUST DIE, in 92 brief pages, dissects the full horror of such a case - apparently based on a true story.This measured account of how a small group of losers decide to make an example of a successful, kind local businessman for a "birthday present" for Hitler, is deeply telling. As the book is so short, I won't provide any further plot summary. The book is mesmeric and effective, particularly in the translation from the French by W Donald Wilson, but is, I think, too short. It reminds me a little of the approach taken by Andrea Maria Schenkel in THE MURDER FARM and ICE COLD, but Chessex conveys more humanity beneath the prose than the clammy novels of Schenkel. I would certainly recommend this book to anyone, particularly to young people not familiar with the lowest common denominator approach that underlay Hitler's evil philosophy. However, I do think that the novella might have been combined with one of the author's other works in the same book, if the price is to be the same as a full-length novel.' - Euro Crime

'According to most conventional views of history the Swiss remained neutral during World War Two. However, even in this land of great natural beauty and idyllic scenery the evil ideology of Nazism gained ardent supporters.

Amongst a small group of Swiss Nazis in the small town of Payerne a plan is hatched to kill a prominent local Jewish businessman. The murder is intended to send out a warning to the Jews of Switzerland of the future they face when the country becomes part of Hitler's Reich. On the 16th of April 1942 just a few days before the Fuhrer's birthday Arthur Bloch a local Jewish cattle merchant is lured into a stable where he is killed with an iron bar by the fanatics.

His body is gruesomely hacked to pieces and then placed in three milk cans and sunk in a local lake. His killers act with coldness and brutality and appear to show no regret about murdering a respected, innocent and well-liked local man of sixty.

Based on real life events, A Jew Must Die is a haunting and searing portrait of anti-Semitic hatred during the Second World War and its horrific consequences. Author Jacques Chessex grew up in Payerne and knew the murderers that he describes and attended the local school with their children.

Chessex brings a painters eye to his descriptions of the Swiss countryside whose beauty he contrasts to great effect with the sickening, festering ideals that it secretly sheltered. His sharp clinical prose is both precise and poetic and his austere wintry tone matches his subject matter perfectly.

Sadly, Chessex, who won the Prix Goncourt in 1973, died recently on the 9th of October 2009. He was a celebrated but controversial literary figure in Switzerland who often explored the darker less palatable aspects of Swiss history. Vivid and beautifully crafted A Jew Must Die is at times shocking in its depiction of the ordinariness of evil. Chessex often asks difficult questions in his work and this sobering rumination on the worst aspects of human depravity is no exception. A horrifying masterpiece.' - Crime Time

'The publication of A Jew Must Die, a novel based on a true story about a murder in his small town of Payerne by the Swiss Goncourt Prize winner Jacques Chessex (Bitter Lemon Press), underscores the Holocaust as a frontier of perspectives on what it means to be human. Now 65 years after World War II's end, the door does not close on the Holocaust, a subject that only continues to resonate, fascinate, and perplex.' - Huffington Post

'When novels, films and television shows claim to be based on a true story, it's often because their plots would otherwise strike readers and viewers as so far fetched they would be unable to suspend disbelief. After all, we demand that fiction make logical sense or, at the very least, be plausible. Yet, often what happens in the real world isn't logical; events occur that shock or puzzle us, especially those involving violence. We don't want to believe that people can do horrific things. Surely, we think, they must have understood what they were doing was wrong. Often, though, these people justify their actions in a way that challenges our beliefs in the basic goodness of humanity.

In his slender novel "A Jew Must Die" (Bitter Lemon Press), Jacques Chessex describes an incident that took place in Switzerland during World War II. In 1942, the Swiss economy is still suffering the aftereffects of the Great Depression. In the country town of Payerne, the unemployed are unhappy and looking for someone to blame. And "who is to blame? The filthy rich. The well-to-do. The Jews and freemasons. They know how to line their pockets, especially the Jews, when factories are closing."

The Swiss Nazis take advantage of the situation, particularly one member of the clergy who encourages group members to do something practical about the Jewish menace. The leader of the Payerne Nazis, Fernand Ischi, decides that in honor of Hitler's upcoming birthday, they will murder someone Jewish. The small group debates which Jew should be chosen, looking for "one highly guilty of filthy Jewishness," and settle on the cattle merchant Arthur Bloch.

In clear, easy-to-read prose, Chessex shows how the Nazi plot develops and the reaction that occurs after Bloch disappears. At first, the non-Jewish Swiss community is callous and uncaring. It is only after Bloch's body is found and the horrific details of his death and dismemberment are released that these upright citizens become dismayed and demand justice. The evil they were unable to see - which, in fact, they dismissed with jokes and innuendos - now comes to haunt them.

"A Jew Must Die" is an unusual conglomerate. Some sections read so dispassionately that they might be a newspaper account. At other times, the novel becomes an ethical commentary on the crime. Particularly moving were the sections written in the first person, when Chessex acknowledges that "I am telling a loathsome story, and feel ashamed to write a word of it. I am ashamed to report what was said: words, a tone of voice, deeds that are not mine but that I make mine, like it or not, when I write." Yet, he feels compelled to tell the story, to describe what happened in his hometown when he was 8 years old. It's an integral part of his personal history that marks him forever.

The last chapter blends both types of storytelling: Chessex not only describes the burial of Bloch's body, but his own personal cry for redemption. This 92-page novel is a heart-rending and moving look at the horror and evil we inflict on each other. Unfortunately, the author's call for pity still remains unheard in heaven and on earth.' - Reporter Group

'Chessex, a prominent Swiss writer, died in 2009 at age 75. He was the first non-French citizen to win the Prix Goncourt, France's most prestigious literary award. American readers of this particular novel, which is one of Chessex's many, will quickly understand why he was so honored. It is a swift and stunning narrative based on a true incident. In the Swiss town of Payenne (the author's hometown), in 1942, a group of Swiss Nazis kill a successful Jewish cattle trader. It was nothing "personal, " as it were, but rather an act of intimidation aimed at the Jewish community of Switzerland at large. This spare but heart-piercing novel illustrates the dementedness of Nazism ( "such a thing as total depravity, pure in its filth ") and also captures the European mind-set of the 1930s and 1940s as people looked for scapegoats to blame for the hard economic times, which in turn made anti-Semitism and thus Nazism appealing. The writing is elegant, in provocative contrast to the human crudity and cruelty it depicts. (This quote captures the atmosphere of the town: "Dark currents flow unseen beneath the assurance and business bustle. Complexions are rosy or ruddy, the soil is rich, but covert dangers lurk. ") Read this novel for the history it captures and for the sheer beauty of its prose'. - Booklist