Janet Todd’s studies of writers such as Jane Austen and Mary Wollstonecraft, coupled with her lifelong passion for less well-known female authors, imbue A Man of Genius with a complete sense of historical verisimilitude. It is easy to forget that this novel is published in 2016, rather than two centuries ago. The reader, however, does not need the same background knowledge as Todd to enjoy each and every gloomy, damp, effluent-spattered page.

Set in 1819, the novel tells the story of Ann St Clair, a spinster in her thirties, living in London, who writes formulaic, ghoulish gothic novels for the mass market, earning herself a decent living in the process. Ann is a very “modern” woman for her time, self-supporting from a young age, her father having mysteriously died before she was born; her mother is an unconventional, narcissistic bully, whose home Ann was only too glad to escape in her teens. We are told that Ann spent some years in an eccentric commune of religious sectarians, where she lost her virginity, before commencing her life as a hack. The book starts with an extract from her latest manuscript:

“Annabella looked at the corpse. Hands and head separate. Blood had leaked from wrists and neck. Fluid covered part of the distorted features. The open eyes were stained so that they glared through their own darkness. A smell of rotting meat.”

And thus we learn from the outset that this is not a woman who is easily shocked.

At a literary gathering to which Ann is invited, she meets Robert James, a dark Byronic figure, outwardly charismatic but inwardly tormented, to whom she is instantly attracted. To his fawning circle of male admirers he is the “man of genius”, though he has yet to produce any real literary masterpiece.

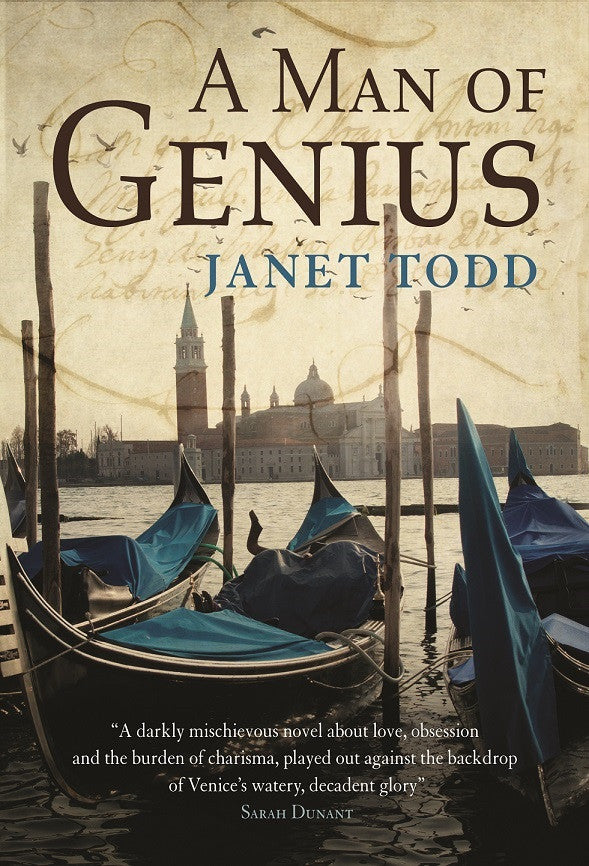

Believing that the atmosphere of Venice will provide him with the stimulus he needs to write his magnum opus, the pair leave London. Robert is hopelessly impractical and so Ann arranges almost everything, seeing to their safety and well-being. The situation does not bode well. Venice, still recovering from its former annexation by Napoleon, and now in the hands of the Austrians, is battle-scarred and impoverished; not gilt-edged, but grey and fogbound, “with its wet floors and dripping walls, its endless tides over slippery feet”. The bodies of the dead, too numerous to be buried, are carried away by the currents of the chilly waterways. Venice in November, if you cannot afford decent lodgings, warm clothes and proper food, soon becomes a living hell, made worse by Robert’s swift descent from moroseness and ill-temper to something far worse. And as the months play out, with the eventual heat of summer come sickness and malady, carried in the fetid, sultry air.

Todd’s depiction of the obsessive psychological warfare between the couple, and of its bewildering outcome, is one of the most disturbing aspects of the novel. Ann’s eventual return to England, via Southern Europe and Paris, offers more opportunities for Todd to give full vent to her gothic-driven imagination, where few situations or characters are quite as they seem. The denouement is unexpected, and a testament to the author’s skills.

As knowledgeable about nineteenth-century history as she is in literature, Todd is clearly fascinated by the period in which the book is set. There are constant references, for example, to Napoleon and his demise, and to the Prince Regent, “obese, extravagant and addicted to laudanum”, and his farce of a marriage to Caroline of Brunswick. Even the title echoes this overall sense of the absurd, for ultimately there is no “man of genius” to be found in these mesmerizing and haunting pages.

Gerri Kimber is a Visiting Professor at the University of Northampton. Her most recent book, a biography of Katherine Mansfield’s early years, is due to be published in September. TLS

The dark side of Venice has always attracted authors, both Italian and international, contrasting the city’s decadence and glory with the hidden underbelly of much of its native population. Locating much of her 19th century story there, Janet Todd captures both its beauty and desperation as her protagonist Ann St Clair, navigates her way as an unwary traveller. Without an excess of description, from La Giudecca to a palazzo, Todd transports the reader so effectively that we can feel the chill November wind coming off the canals or suffer the unforgiving heat of the summer when those who can afford to escape to cooler climes. Her Venice – a city of more darkness than light – lingers in the mind. As the title announces, this novel concerns a man of genius – or so he and his male friends believe, as at first does St Clair. The heart of the story is, unfortunately, timeless: an apparently strong, independent woman falling for the charms of a man who proves to be increasingly destructive to himself and her as she persists in clinging on. Todd explores the obsession of St Clair with the boorish and brutish Robert James as she pretends to live as his wife in Venice – never wanting to give up on him – so effectively that one wonders if she writes from experience. A dark memory would explain why she fails to paint James as particularly attractive even at the beginning, so that it is difficult to fully understand why St Clair is so tied to the man whose only touch is a violent beating. Todd also brings her knowledge and affection for female writers of yesteryear into play. Ann St Clair, a young woman of indeterminate parentage who has to make her own way in the world, pens cheap gothic novels. These are mirrored in the plot. The writing is studded with such allusions and a deep know ledge of the history and thinking of the period permeates much of the book’s dialogue. Ultimately, a book has to work as a story, not merely writing to be admired, and Todd just manages this, although it drags in parts. However, like any good gothic novel, the final chapters are page turners as St Clair discovers both her past and her destiny. Tribune Books

Todd’s academic expertise on women writers and the Romantic period serves her well in this gripping, original historical novel with abundant thrills, spills and revelations.

Ann (perhaps a nod to Ann Radcliffe), the independent-minded protagonist, is a writer of successful, melodramatic, populist Gothic novels featuring innocent women pursued by manipulative villains. She falls head over heels into an obsessive passion for narcissistic, Romantic idealist and poet Robert James (a cross between Shelley and Lord Byron). His self-acknowledged genius conceals the darkness of madness and violence, as she discovers in Venice. Forced to flee or be consumed by this destructive relationship, she makes major discoveries about her psychological and social identity, like the typical heroine of her own and others’ Gothic novels.

A powerful sense of atmosphere is conjured up through Todd’s detailed descriptions, whether the setting is 1819 Regency London or Venice, while the vivid depiction of everyday life’s ephemera, the racy dialogue and elaborate mannerisms, all sound and feel authentic. Steve Barfield. The Lady

When Ann St. Clair, a writer of gothic novels, first meets Robert James at a literary gathering, she, like all his Grub Street friends, is awed by his brilliance. Her admiration deepens into something much more powerful and intimate, but as the couple flee to post-Napoleonic Europe in search of freedom of expression and inspiration, Robert’s brilliance deteriorates into mania and paranoia. Like her heroines, Ann finds herself trapped in a hopelessly dark and complex web of dependence and fear that though it is of her own making is no less deadly. Making her fiction debut, noted British literary scholar Todd has crafted a psychologically haunting and disturbing tale as full of mystery, exotic foreign places, and questions of parentage as any penned by her protagonist, whose journey back to understanding and shaky self-reliance (after a fortuitous rescue by a mysterious stranger) is almost antigothic in its conclusion.

Verdict Devotees of Ann Radcliffe (The Mysteries of Udolpho) and other authors of the gothic literary tradition will enjoy this atmospheric novel.—Cynthia Johnson, formerly with Cary Memorial Lib., Lexington, MA Library Journal

Women struggling to make their way in a man’s world are the heroines of several recent historical novels. In A Man of Genius, the debut novel by the academic and literary biographer Janet Todd (Bitter Lemon), the central character, Ann, maintains a precarious independence in Regency England by writing gothic romances. When she meets Robert James, a self-proclaimed genius, she is initially seduced by his charisma, but a lengthy sojourn in Venice opens her eyes to his many failings. More a petulant windbag than the prodigy he and his taproom disciples believe him to be, Robert is a poor vehicle for Ann’s hopes for love and fulfilment. Amid the intrigue of Venice, she has to find her own path to redemption. This is a haunting, sophisticated story about a woman slowly discovering the truth about herself and the elusive, possibly illusive, nature of genius. Sunday Times

Ann St Clair is determined not to follow the ways of her Georgian contemporaries into marriage. She earns enough as a writer of Gothic romances to keep the wolf from the door and believes that's how it will always be. Then she meets Robert James, writer, self-acclaimed genius and popular raconteur, becoming totally besotted. However Ann still thinks she can retain her independence, even when she goes to Venice with Robert to escape the boredom of English life. However there's a darker side to this man, the unforeseen consequences of which will unlock the mysteries of Ann's own childhood.

Welsh born Janet Todd OBE is an academic whose field of expertise is women writers and the depiction of women in literature. Over the years Janet has brought out 35 extremely well received critical books and essay collections about such women as Jane Austen, Aphra Behn and Mary Shelley. It's therefore fitting that, if there's a fictional tale to be written about an early 19th century gothic romance author, Janet writes it while mimicking the style of 19th century gothic romance.

A Man of Genius begins with Ann's first encounters with James alongside flashbacks from her unusual childhood. Ann's father died before she was born and she grows up feeling unloved, distanced and side-lined by her mother. Indeed this isn't a book we'd pick up if we fancied a giggle but the characters are so well observed we're drawn into their world.

Although Ann St Clair may have ideas beyond her century they're trapped within the accepted spectrum of the contemporary mores. For instance it's interesting that the marriage-abhorring Ann unilaterally feigns marriage to Robert James while they're abroad. Part of this may be a nod to her affection causing a rethink but part is due to it making life easier.

Janet also cleverly contrasts Ann's life and expectations with those of Ann's cousin Sarah. Sarah's expectations and morals are very much those of the contemporary establishment. Sarah's place is to support her husband and birth/raise children. This isn't her first choice of lifestyle nor one at which she feels particularly adept. Therefore the subtle hints are there that this could be seen as a form of socially legitimised abuse. It's easy to look at the past with modern knowledge and outlook but even if we discount Sarah's unchosen compliance, Ann seems to be having a rougher time of it.

When it comes to the story of Ann and her dark brooding man, we soon realise it's not going to be as romantic as Jane Eyre and Rochester. As the narration is intertwined with Ann's own inner monologue and analysis, we see there are times when she almost becomes Robert's stalker before the tables turn in Venice. What happens when the self-proclaimed genius falls short of his own standards? We and Ann find out, explosively.

We read through around 200 pages of story threaded with introspection. Then we realise it's a book of two halves, the introspection lessens, suddenly launching us into a twisting adventure. It may seem predictable as we may think we know the answers to the puzzles that Janet's laid before us but the answers aren't as simple as our guesses.

If you enjoy escapism historical fiction during which you can turn your brain off, this may not be for you. On the other hand if you fancy something a bit different with scenes to ponder set against a dark background, it definitely rates a place on your reading list. The BookBag

Drawn to Fiction: Janet Todd’s A Man of Genius, by Lucinda Byatt

Janet Todd is a distinguished academic and literary historian.1 Now retired, she lives for part of the year in Venice. What, I wondered, had prompted her to embark on a new journey by writing her first novel? Surprisingly, Todd admits that she has always been drawn to fiction.

When I was a student in the ‘60s a tutor told me to go and be a novelist when I half-heartedly suggested I should apply to become a solicitor. I became an academic in the US for financial reasons and because the American feminist movement inspired me to do excavating work on early women writers. I think my biographies have had a tendency towards fiction and I’ve certainly had to rein in speculation! As soon as I escaped from full-time work, I’ve turned to the form I’ve always loved best.

The result is A Man of Genius, a book described by Todd’s publisher, Bitter Lemon Press, as “a work of psychological fiction.” The historical setting of the two cities where the novel is mainly set, London and Venice in 1816–21, is evocatively described. Caroline of Brunswick, then the Princess of Wales, is a favourite subject for gossips, such as the protagonist’s mother and her widowed friends. Ann St Clair is a complex figure: she craves the affection of Robert James, a “man of so much promise,” a magnetic (but strangely repulsive) character, the author of a single fragment, an unfinished work on Attila the Hun. Todd certainly captures Ann’s complete infatuation as the ill-assorted pair set off on a reckless journey to Venice, ostensibly motivated by Robert’s search for creative inspiration. Ann’s inspiration has far more mundane origins: she writes cheap gothic novels, modelled on the likes of Mrs Radcliffe, whose heroine in The Mysteries of Udolpho sees Venice through an improbable “saffron glow.” Todd confirmed that the character of Ann was not inspired by a single woman writer.

For many years I’ve worked on early women writers and been fascinated by the increase in numbers at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth centuries. They fed the taste for gothic and sensational fiction while modestly avoiding claims to being artists – usually they said they wrote for money because they lacked a male breadwinner. My character Ann is like one of the hack writers of the horrid novels that so entranced Catherine Morland in Northanger Abbey.

Two of my latest biographies, of the 1790s feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and her daughter Fanny (along with her sister, later Mary Shelley), have dealt with a fatal passion of women for men they invested with imaginary qualities.2 I’ve not followed the trajectory of the biographies towards suicide, but my reading of these lives helped inform my creation of Ann St Clair.

The Venice where Ann and Robert arrive in 1819 is not the resplendent city of, say, the sixteenth or the seventeenth century, but altogether a sadly diminished place, its proud independence first despoiled by Napoleon and now suffocated under Austrian rule. Todd’s intimate knowledge of Venice reveals an absorbing picture. Ann gets to know the city and its inhabitants through her tutee, Beatrice Savelli, and the mysterious Giancarlo Scrittori and his friends. She grows fond of the “tawdry glamour” of the city, “its gaiety, its insouciance about its failure of nerve.” Even the freezing cold and later the oppressive heat, the rotten wood and the broken stone cannot detract from the beauty of the lagoon birds whose names Scrittori teaches her.

In A Man of Genius Todd explores the idea of the downfall of the divinely inspired, “almost invariably male” poet, a figure that “became a cultural cliché in the Regency.” Robert is so all-consumed by his art that he despises the fame and adulation received by another contemporary, Byron, who also spent some months in Venice. As fear of failure grows, violent abuse and hatred fill the void of Robert’s creativity. Ultimately, perhaps, Todd is exploring the nature of genius that borders on madness, “aspects of our present cult of celebrity with its acceptance of destructive behaviour in cultural icons.” Historical Novels Society

Anyone who’s studied, or taken an interest in, women writers of the 18th and 19th centuries will have encountered the work of Janet Todd. She has written biographies of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley, and edited and written on the works of Jane Austen, Aphra Behn and many others. A Man of Genius is her first foray into fiction, and a terrific début it is.

The year is 1819. Ann St Clair, a single woman but not an inexperienced one (she once lived with a man on a sort of commune in the country), lives on her own in London and is a professional writer of Gothic novels. Much to her regret she never knew her father Gilbert, though according to her mother he was a remarkable man. The only family member she keeps in touch with is her kindly, conventional, married cousin Sarah, but her social life revolves around a group of young, radical writers and artists who meet once a week for dinner. It’s here one evening that she meets Robert Hughes, who is reputed to be a genius on the basis of the only thing he has written, a fragment called Attilla. Robert’s intense philosophical conversation keeps the rest of the guests spellbound, and Ann is completely swept away. It’s not long before she and Robert become a couple, though the relationship is not without its problems. However, when he expresses the intention of moving to Venice, Ann naturally goes with him.

Life in Venice may sound romantic, but it proves to be the very opposite:

“They followed the padrona up sloping steps of damp uneven stone, leaving a ragged boy scarcely in his teens to carry up the trunks. At length they entered a large, piercingly cold room with a high ceiling crossed by dark, crudely cut wooden beams. She’d thought Italy would be warm. Another lie of poetry and novels, the warm south that wasn’t warm. It was only November. It must get worse.”

There is not enough money for good lodgings, the climate is either cold or unpleasantly hot, and Robert, who thought a change of scene might give him the inspiration he lacked in London, finds it impossible to write. He sits at his desk day after day with piles of paper and pens, but when Ann manages to read what he has written, it is incomprehensible banalities. His moods, which have always been dark, intensify, and he frequently subjects Ann to verbal and physical abuse. Ann’s time is spent trying to keep the household from complete deterioration, earning a litte money by teaching English to a young girl who lives in a grand palazzo, and encountering some mysterious and rather suspect Venetians and expatriates. As Robert starts to become more and more obviously mentally unstable, so Ann’s state of mind edges closer and closer to total despair. Even when circumstances make it necessary for her to journey back to England, she is in no shape for the hardships of the circuitous route she is forced to take, and it is questionable at times whether she will survive.

There’s so much to enjoy here. The story is an exciting one, with plenty of mysteries and revelations, including the vital question of Ann’s parentage and the true identity of her absent, unknown father. The period detail is faultless and the pictures of London, Paris, Venice and places in between wholly convincing. But above all, the novel depicts something which exists as much today as it did in Ann’s own time – a clever woman’s obsession with a man who mistreats and abuses her, and the effect this has on her increasingly fragile psychology. Ann has always suffered from a sense of inferiority, and has never felt loved or valued by her difficult, uncommunicative mother, so her self-worth is low to start with and it’s only too easy for her to sink into a despairing dependence on her abuser. Even her eventual rescue by a mysterious stranger is fraught with problems and uncertainties, and when she finally gets some answers to her abiding questions, they are hardly comforting.

I've made this sound as if it might be rather dark and depressing – well, dark it may be at times, but depressing it certainly is not. I galloped through it, anxious for Ann and wishing her well, and uncertain until the very end how things would turn out for her. Shiny New Books

What happens when an eminent scholar and biographer turns her hand to fiction? In the case of Janet Todd’s A Man of Genius, we get a highly distinctive, engrossing tale of mystery and madness, centering on a woman writer of one of those “horrid books” that were so popular around Jane Austen’s time. In Todd’s novel, Ann St. Clair has no respect for her own writing, seeing it only as a profitable and not too unpleasant way to make a living. She’s also glad to be independent of her uncaring, distant mother, who is entirely wrapped up in the memory of her dead husband.

The gothic elements of Ann’s fiction start to intrude into her own life, though, when she tumbles into a bizarre relationship with a male writer whose friends think him a genius-in-waiting, based on his one fragmentary work. Haunted by the bitter ghosts of her childhood, tying herself to an increasingly unstable man who neither needs nor wants her, Ann trails him across the post-Napoleonic landscape of Europe to a strange, shadowy existence in the underworld of Venice. The conclusion is shattering, surprising, and for me, unforgettable.

Ann’s story is not a comfortable or easy one to read, and this is not an amusing historical pastiche. Todd takes us into the dark heart of nineteenth century London and Venice, following her protagonist into a horrible form of emotional and physical subjugation. Her journey is harrowing, violent, and sad, and readers must have a strong stomach to follow her through to the teasingly hopeful end. But for those who do, the journey into the depths becomes a confirmation of the power of the self, which sometimes only lights up when threatened by utter eclipse.

Todd doesn’t attempt an imitation of the writing of the time — we are looking over the characters’ shoulders from a modern perspective, as it were — and yet her highly mannered style chimes well with the historical period. One can tell that she has immersed herself in it to such an extent that she can play freely with its language and people and ideas, so that her creation is relevant to both the “then” of the story and the “now” in which we experience it.

I usually avoid books that are gleefully advertised as “dark” and “harrowing,” as I dislike the kind of prurient pleasure-in-others’-pain that they often seem to trade on, but Ann’s story offers something more complex and far more interesting than that. As we move with Ann from the fragmentary to the whole, from blind folly to a hard-won wisdom, we are touched by some of the deepest mysteries of the human heart. Janet Todd has beautifully translated her passion for and knowledge of the era and its literature into a compelling fictional creation. I hope she will give us many more. Emerald City